The Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) is a self-contained individual United States military ration used by the United States Armed Forces and Department of Defense. It is intended for use by American service members in combat or field conditions where other food is not available. MREs have also been distributed to civilians as humanitarian daily rations during natural disasters and wars.[1]

The MRE replaced the canned Meal, Combat, Individual (MCI) in 1981.[2] Its garrison ration and group ration equivalent is the Unitized Group Ration (UGR), its in-combat and mobile equivalent is the First Strike Ration (FSR), and its long-range and cold weather equivalents are the Long Range Patrol (LRP) and Meal, Cold Weather (MCW) respectively.

History

Predecessors

| External video | |

|---|---|

The first American military ration established by a Congressional Resolution, during the Revolutionary War, consisted of enough food to feed a man for one day, mostly beef, peas, and rice.[3] During the Civil War, the U.S. military moved toward canned goods. Later, self-contained kits were issued as a whole ration and contained canned meat, bread, coffee, sugar and salt. During World War I, canned meats were replaced with lightweight preserved meats (salted or dried) to save weight and allow more rations to be carried by soldiers on foot. At the beginning of World War II, a number of new field rations were introduced, including the Mountain ration and the Jungle ration. Cost-cutting measures by Quartermaster Command officials during the latter part of World War II and the Korean War again saw the predominance of heavy canned C-rations issued to troops, regardless of operating environment or mission.[4] During World War II, over 100 million cans of Spam were sent to the Pacific.[5] The use of canned wet rations continued through the Vietnam War, with the improved MCI.

During the Vietnam War, problems with the canned MCI rations become apparent. MCI cans were heavy and bulky; they could not fit easily in a uniform pocket and could even cause injury. The cans could also corrode in the tropical environment and cause the food to spoil. After the food was consumed, the empty cans were difficult to dispose of; the littered cans were sometimes fashioned into booby traps by the enemy. Finally, the MCI rations had an estimated shelf life of 24 months at 70 °F (21 °C), which was found to be inadequate as supply was often interrupted by weather and enemy activity.[6]

Introduction

After repeated experiences with providing prepared rations to soldiers dating from before World War II, Pentagon officials ultimately realized that simply providing a nutritionally balanced meal in the field was not adequate. Service members in various geographic regions and combat situations often required different subsets of ingredients for food to be considered palatable over long periods. Catering to individual tastes and preferences would encourage service members to actually consume the whole ration and its nutrition. Most importantly, the use of specialized forces in extreme environments and the necessity of carrying increasingly heavy field loads while on foot during long missions required significantly lighter alternatives to standard canned wet rations.

In 1963, the DoD began developing the "Meal, Ready to Eat", a ration that would rely on modern food preparation and packaging technology to create a lighter replacement for the canned MCI. In 1966, this led to the Long Range Patrol, or LRP ration, a dehydrated meal stored in a waterproof canvas pouch. As with the Jungle ration, its expense compared to canned wet rations, as well as the costs of stocking and storing a specialized field ration, led to its limited usage and repeated attempts at discontinuance by Quartermaster Command officials.[4]

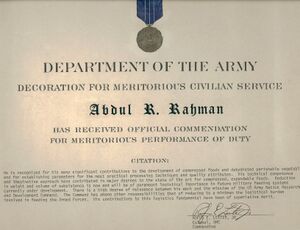

Early MRE prototypes that involved freeze-dried and dehydrated foods were developed under Abdul Rahman, who later received the Meritorious Civilian Service Award for his work.[7] Further work was needed to develop a ration that did not require re-hydration (thus not requiring additional preparation time and water). Further effort, led by Rauno A. Lampi, Chief of Food Systems Equipment Division at the Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, concentrated on the refinement of the retort pouch to contain a wet ration with a three-to-ten year shelf life that could be easily shipped, carried in the field, opened and consumed straight out of the package if necessary with no further heat or water. The resulting MRE went into special issue starting in 1981 and standard issue in 1986, using a limited menu of twelve entrées.[8]

Ongoing development

The MRE has been in continuous development since its introduction.

After the introduction of the MRE, service members often often heated the food by boiling them in a canteen cup over a lit fuel source. This was slow, especially in cold weather. It also produced a visible flame that was undesirable at night. Service members strongly desired a more convenient way to heat the food. Between 1988-1989, development and testing was conducted for a new flameless ration heater. In 1990, the Flameless Ration Heater (FRH) was introduced. Service members activate a chemical reaction with a few ounces of water, which produces an exothermic reaction. An FRH was included with each meal beginning with the MRE XIII in 1993.[9]

In an array of field tests and surveys, service members requested more entrée options and larger serving sizes. By 1994, commercial-like graphics were added to make the packets more user-friendly and appealing, while biodegradable materials were introduced for inedible components, such as spoons and napkins. The number of main dishes expanded to 16 by 1996 (including vegetarian options), 20 by 1997 and 24 by 1998. As of 2023, the system includes 24 entrées, and more than 150 additional items.[10] The variety allowed service members to trade them in order to find something palatable for various cultures and geographical regions.

The ration originally came in a dark brown outer bag from 1981 to 1995 because it was designed for service in the temperate forests and plains of central Europe. It was replaced in 1996 with a tan outer bag that was better suited for service in the deserts of the Middle East. By 2000, a bean burrito main dish was introduced.[11] In 2006, "Beverage Bags" were introduced to the MRE, as service members have begun to depend more on hydration packs than on canteens, thus denying them the use of the metal canteen cups (shaped to fit in a canteen pouch with the canteen) for mixing powdered beverages. In addition to having measuring marks to indicate levels of liquid for precise measurement, they can be sealed and placed inside the flameless heater.

Most recently, MREs have been developed using the Dietary Reference Intake, created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM indicated service members (who were classified as highly active men between the ages of 18 and 30) typically burn about 4,200 Calories (kcal) a day, but tended to only consume about 2,400 Calories a day during combat, entering a negative energy balance. This imbalance occurs when service members fail to consume full portions of their rations.[12] Although manipulations to the food items and distribution of macronutrients to help boost the amount of kilocalories per MRE have been made, more studies are showing many service members still do not meet today's standards of daily consumption, often trading and discarding portions of the ration.[13] Researchers continue to study the habits and eating preferences of service members, making constant changes that encourage service members to eat the entire meal and thus get full nutritional value.[13] A small randomized controlled trial from 2017 confirms the nutritonal balance of MRE eaten-in-whole using blood tests.[14]

The military has experimented with new assault ration prototypes, such as the First Strike Ration and the HOOAH! Bar, designed with elite or specialized forces in mind. Lighter than the typical MRE, they require no preparation and allow service members to eat them while traveling.[15] In July 2009, 6,300 dairy shake packets of varying flavors were recalled due to evidence of Salmonella contamination.[16]

Requirements

Each meal provides about 1,200 calories (5,000 kJ).[17] They are intended to be eaten for a maximum of 21 days (the assumption is that logistics units can provide fresh food rations by then), and have a minimum shelf life of three years (depending on storage conditions).[18]

Packaging requirements are strict. MREs must be able to withstand parachute drops from 380 metres (1,250 ft), and non-parachute drops of 30 metres (98 ft). The packaging is required to maintain a minimum shelf life of three and a half years at 27 °C (81 °F), nine months at 38 °C (100 °F), and short durations from −51 °C (−60 °F) to 49 °C (120 °F) must be sustainable. New forms of packaging are being considered to better meet these requirements including the use of zein to replace the foil, which can be easily punctured, conducts heat, and is reflective (which may give away a servicemember's position).[19]

Each MRE weighs 510 to 740 grams (18 to 26 oz), depending on the menu.[13] Since MREs contain water, they weigh more than freeze-dried meals providing equivalent calories.

Resale status

As a result of earlier unauthorized sales to civilians, the Department of Defense requires that "U.S. Government Property, Commercial Resale is Unlawful" be printed on each case of MREs.[20] The warning is only intended for service members as there are no laws that forbid the resale of MREs by civilians.[21] Although the government has attempted to discourage sellers from selling MREs,[22] auction sites such as eBay have continued to allow auctions of the MREs because the Department of Defense has been unable to show them any regulations or laws specifically outlawing the practice. According to a spokesman for eBay, "until a law is passed saying you can't sell these things, we're not going to stop them from being sold on the site."[23] Therefore, while MREs are not prima facie contraband, the procurement and sale of MREs by military personnel for personal profit is illegal under the Uniform Code of Military Justice Article 108.[24] As a result, MREs found for sale outside reputable vendors often fall into a grey market where the question of how it entered civilian hands (through theft/legitimate means) and/or its quality may be unknown.

An investigation conducted in 2006 on behalf of the US Government Accountability Office determined multiple instances where sellers on eBay may have improperly obtained MREs and sold them to the public for private gain.[20] As military MREs are procured at taxpayers' expense, they are intended to be consumed by individuals from authorized organizations and activities. Consequently, "if military MREs are sold to the general public on eBay, then they are clearly not reaching their intended recipients and represent a waste of taxpayer dollars and possible criminal activity."[20] Further, MREs found on eBay are typically older and closer to their expiration date, having been sourced in "neighborhood yard sales" and "Marine base dumpsters."[20]

The growth of MREs listed on eBay in 2005 resulted in a government investigation of whether they were intended for Hurricane Katrina victims, and the news media nickname "Meals Ready for eBay."[25] Some cases were being sold from Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida and other Gulf states affected by Katrina. The internal cost of a 12 pack case of MREs is $86.98 (approx. $7.25 a meal) to the government, much higher than what is paid to vendors.[25] MREs can be purchased by civilians directly from the contractors who supply MREs to the United States Government. These MREs usually omit the flameless ration heater and have other minor differences (i.e., design of case and bag or type of spoon), but otherwise are often very similar to genuine US Government MREs.[26][27]

In the Philippines, the government stopped MREs from being sold in local markets.[28]

Contents

General contents may include:[29]

- Main course (often referred to as "the main")

- Side dish

- Dessert or snack (often commercial candy, fortified pastry, first strike bar, or Soldier Fuel Bar.)

- Crackers or bread

- Spread of cheese, peanut butter, or jelly

- Powdered beverage mix: fruit flavored drink, cocoa, instant coffee or tea, sport drink, or dairy shake.

- Utensils (in rare occasions, a full set is included – with a spoon, fork and knife – but most commonly only a plastic spoon is given)

- Flameless ration heater (FRH)

- Beverage mixing bag

- Accessory pack:

- Xylitol chewing gum

- Water-resistant matchbook

- Napkin / toilet paper

- Moist towelette

- Seasonings, including salt, pepper, sugar, creamer, and/or Tabasco sauce

- Freeze dried coffee powder

Many items are fortified with nutrients. In addition, DoD policy requires units to augment MREs with fresh food whenever feasible, especially in training environments.

To make MREs more palatable to service members and match ever-changing trends in popular tastes, the military is constantly seeking feedback to adjust MRE menus and ingredients. In the following list, only main entrees are listed.[30] Vegetarian menus are marked and footnoted on their first appearance.[veg 1]

| Menus 1981 to 1997 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | MRE I – VII (1981–87) | MRE VIII – XII (1988–92) | MRE XIII – XIV (1993–94) | MRE XV (1995) | MRE XVI (1996) | MRE XVII (1997) |

| 1 | Pork Patty | Pork w/ Rice in BBQ Sauce | Pork w/ Rice in BBQ Sauce | Pork w/ Rice in BBQ Sauce | Beef Steak | Beef Steak |

| 2 | Ham & Chicken loaf | Corned Beef Hash | Corned Beef Hash | Chili w/ Macaroni | Tuna w/ Noodles | Boneless Pork Chop w/ Noodles |

| 3 | Beef Patty (nicknamed "Hockey Puck") |

Chicken Stew | Chicken Stew | Chicken Stew | Chicken Stew | Chicken Stew |

| 4 | Beef slices in BBQ sauce | Omelet with Ham | Omelet with Ham | Grilled Chicken | Ham Slice | Ham Slice |

| 5 | Beef Stew | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Chicken w/ Noodles |

| 6 | Frankfurters w/ Beans (nicknamed "Four Fingers of Death") |

Chicken a la King | Smokey Franks | Smokey Franks | Smokey Franks | Smokey Franks |

| 7 | Turkey Diced w/ Gravy (nicknamed "Wild Turkey Surprise") |

Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Pork Chow Mein |

| 8 | Beef Diced w/ Gravy | Ham Slice | Ham Slice | Ham Slice | Chicken w/ Rice | Chicken w/ Rice |

| 9 | Chicken à la King | Meatballs w/ Tomato Sauce | Pork Chow Mein | Pork Chow Mein | Pork Chow Mein | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Meatballs & BBQ sauce | Tuna w/ Noodles | Tuna w/ Noodles | Tuna w/ Noodles | Chili w/ Macaroni | Chili w/ Macaroni |

| 11 | Ham slices | Chicken w/ Rice | Chicken w/ Rice | Chicken w/ Rice | Pasta w/ Vegetables[veg 1] | |

| 12 | Ground Beef w/ Spiced Sauce | Escalloped Potatoes w/ Ham | Escalloped Potatoes w/ Ham | Escalloped Potatoes w/ Ham | Cheese Tortellini[veg 1] | Cheese Tortellini |

| 13 | Chicken Loaf (12B; discontinued 1986) | Pork w/ Rice | Pork w/ Rice | |||

| 14 | Beefsteak (9B; discontinued 1982) | Chicken Parmesan | Chicken Parmesan | |||

| 15 | Grilled Chicken | Grilled Chicken | ||||

| 16 | Escalloped Potatoes w/ Ham | Tuna w/ Noodles | ||||

| 17 | Beef Ravioli | |||||

| 18 | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | |||||

| 19 | Beef w/ Mushrooms | |||||

| 20 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | |||||

| Menus 1998 to 2003 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | MRE XVIII (1998) | MRE XIX (1999) | MRE XX (2000) | MRE XXI (2001) | MRE XXII (2002) | MRE XXIII (2003) |

| 1 | Beef Steak | Beef Steak | Grilled Beefsteak | Grilled Beefsteak | Beefsteak w/ Mushrooms | Beefsteak w/ Mushrooms |

| 2 | Boneless Pork Chop w/ Noodles | Boneless Pork Jamaican | Boneless Pork Chop | Boneless Pork Chop | Jamaican Pork Chop w/ Noodles | Pork Rib |

| 3 | Chicken Stew | Beef Teriyaki | Beef Teriyaki | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli |

| 4 | Ham Slice | Ham Slice | Country Captain Chicken (nicknamed "KKK") |

Country Captain Chicken | Country Captain Chicken | Country Captain Chicken |

| 5 | Chicken w/ Noodles | Grilled Chicken Breast | Grilled Chicken Breast | Grilled Chicken Breast | Grilled Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast |

| 6 | Grilled Chicken | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Thai Sauce | Chicken w/ Thai Sauce | Chicken w/ Thai Sauce |

| 7 | Pork Chow Mein | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa |

| 8 | Chicken w/ Rice | Chicken w/ Rice | Chicken and Rice | Chicken and Rice | Beef Patty | Beef Patty |

| 9 | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Chili w/ Macaroni | Chili w/ Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni |

| 11 | Pasta w/ Vegetables | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce[veg 1] | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce |

| 12 | Cheese Tortellini | Rice & Bean Burrito[veg 1] | Rice & Bean Burrito | Rice & Bean Burrito | Rice & Bean Burrito | Black Bean & Rice Burrito[veg 1] |

| 13 | Thai Chicken | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini |

| 14 | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Alfredo Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Alfredo Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Alfredo Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Alfredo Sauce | Manicotti w/ Vegetables[veg 1] |

| 15 | Beef Franks | Beef Franks | Beef Frankfurters | Beef Enchilada | Beef Enchilada | Beef Enchiladas |

| 16 | Bean & Rice Burrito | Chicken w/ Thai Sauce | Thai Chicken | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles |

| 17 | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Teriyaki | Beef Teriyaki | Beef Teriyaki |

| 18 | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes | Turkey Breast w/ Gravy & Potatoes |

| 19 | Beef w/ Mushrooms | Beef w/ Mushrooms | Beef w/ Mushrooms | Beef w/ Mushrooms | Beef w/ Mushrooms | Roast Beef |

| 20 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce |

| 21 | Beef Teriyaki | Chicken Stew | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chicken Tetrazzini |

| 22 | Chicken w/ Salsa | Pork Chow Mein | Pork Chow Mein | Jambalaya | Jambalaya | Jambalaya |

| 23 | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli |

| 24 | Pasta w/ Alfredo Sauce[veg 1] | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy |

| Menus 2004 to 2009 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | MRE XXIV (2004) | MRE XXV (2005) | MRE XXVI (2006) | MRE XXVII (2007) | MRE XXVIII (2008) | MRE XXIX (2009) |

| 1 | Beef Steak | Beef Steak | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans |

| 2 | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib |

| 3 | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli |

| 4 | Country Captain Chicken | Cheese & Vegetable Omelet[veg 1] | Cheese & Vegetable Omelet | Cheese & Vegetable Omelet | Cheese & Vegetable Omelet | Maple Sausage |

| 5 | Grilled Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast | Chicken Breast |

| 6 | Chicken w/ Thai Sauce | Chicken Fajitas | Chicken Fajitas | Chicken Fajitas | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles |

| 7 | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Chicken w/ Salsa | Meatloaf w/ Gravy | Beef Brisket |

| 8 | Beef Patty | Beef Patty | Beef Patty | Beef Patty | Beef Patty | Beef Patty |

| 9 | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Tuna | Tuna in Pouch | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni |

| 11 | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce | Pasta w/ Vegetables in Tomato Sauce | Spicy Penne Pasta[veg 1] | Vegetable Manicotti | Vegetable Lasagna[veg 1] | Vegetable Lasagna |

| 12 | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce[veg 1] | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce |

| 13 | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini |

| 14 | Manicotti w/ Vegetables[veg 1] | Manicotti w/ Vegetable | Manicotti w/ Vegetable | Spicy Penne Pasta w/ Vegetarian Sausage[veg 1] | Spicy Penne Pasta w/ Vegetarian Sausage | Spicy Penne Pasta w/ Vegetarian Sausage |

| 15 | Beef Enchiladas | Beef Enchiladas | Beef Enchiladas | Beef Enchiladas | Beef Enchiladas | Beef Enchiladas |

| 16 | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken w/ Noodles | Chicken Fajita | Chicken Fajita | Chicken Fajita |

| 17 | Beef Teriyaki | Sloppy Joe Filling | Sloppy Joe | Sloppy Joe Filling | Sloppy Joe Filling | Sloppy Joe Filling |

| 18 | Cajun Rice, Beans & Sausage | Cajun Rice & Sausage | Cajun Rice, Beans, & Sausage | Meatballs w/ Marinara | Meatballs w/ Marinara | Meatballs w/ Marinara |

| 19 | Roast Beef | Roast Beef w/ Vegetables | Roast Beef w/ Vegetables | Pot Roast w/ Vegetables | Pot Roast w/ Vegetables | Pot Roast w/ Vegetables |

| 20 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce |

| 21 | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chicken Tetrazzini | Chili & Macaroni | Tuna in Pouch | Tuna in Pouch |

| 22 | Jambalaya | Jambalaya | Jambalaya | Chicken w/ Dumplings | Chicken w/ Dumplings | Chicken w/ Dumplings |

| 23 | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken w/ Cavatelli | Chicken Pesto & Pasta | Chicken Pesto & Pasta |

| 24 | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Meat Loaf w/ Gravy | Chicken w/ Salsa | Buffalo Chicken |

| Menus 2010 to 2015 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | MRE XXX (2010) | MRE XXXI (2011) | MRE XXXII (2012) | MRE XXXIII (2013) | MRE XXXIV (2014) | MRE XXXV (2015) |

| 1 | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans |

| 2 | Pork Rib | Chicken Fajita | Chicken Fajita | Chicken Fajita | Shredded BBQ Beef | Shredded BBQ Beef |

| 3 | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Chicken with Noodles | Chicken with Noodles | Chicken with Noodles | Chicken with Noodles |

| 4 | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage | Pork Sausage w/ Gravy | Pork Sausage w/ Gravy | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce |

| 5 | Mediterranean Chicken | Mediterranean Chicken | Chicken, Tomato, Feta | Mediterranean Chicken | Mediterranean Chicken | Diced Chicken |

| 6 | Chicken w/ Noodles | Beef Patty | Beef Roast w/ Vegetables | Beef Taco | Beef Taco | Beef Taco |

| 7 | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket |

| 8 | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce |

| 9 | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni |

| 11 | Vegetable Lasagna | Vegetable Lasagna | Vegetable Lasagna | Vegetable Lasagna | Vegetarian Taco Pasta[veg 1] | Vegetarian Taco Pasta |

| 12 | Veggie Burger w/ BBQ Sauce | Spicy Penne Pasta[veg 1] | Spicy Penne Pasta | Spicy Penne Pasta | Spicy Penne Pasta | Spicy Penne Pasta |

| 13 | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini |

| 14 | Spicy Penne Pasta w/ Vegetarian Sausage | Ratatouille[veg 1] | Ratatouille | Ratatouille | Ratatouille | Ratatouille |

| 15 | Southwest Beef & Black Beans | Southwest Beef & Black Beans | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew |

| 16 | Chicken Fajita | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib | Pork Rib |

| 17 | Sloppy Joe | Pork Sausage w/ Gravy | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage |

| 18 | Beef Patty | Chicken w/ Noodles | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli |

| 19 | Beef Roast w/ Vegetables | Beef Roast w/ Vegetables | Sloppy Joe | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty |

| 20 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Pork Sausage w/ Gravy | Hash Brown Potatoes w/ Bacon |

| 21 | Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna |

| 22 | Chicken and Dumplings | Sloppy Joe | Asian Beef Strips | Asian Beef Strips | Asian Beef Strips | Asian Style Beef Strips w/ Peppers |

| 23 | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta |

| 24 | Buffalo Chicken | Buffalo Chicken | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans |

| Menus 2016 to 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | MRE XXXVI (2016) | MRE XXXVII (2017) | MRE XXXVIII (2018) | MRE XXXIX (2019) | MRE XL (2020) |

| 1 | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans | Chili w/ Beans |

| 2 | Shredded BBQ Beef | Shredded BBQ Beef | Shredded BBQ Beef | Shredded BBQ Beef | Shredded BBQ Beef |

| 3 | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables |

| 4 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce |

| 5 | Chili and Macaroni | Chicken Chunks | Chicken Chunks | Chicken Chunks | Chicken Chunks |

| 6 | Beef Taco | Beef Taco | Beef Taco | Beef Taco | Beef Taco |

| 7 | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket | Beef Brisket |

| 8 | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce |

| 9 | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Chicken Chunks | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni | Chili and Macaroni |

| 11 | Vegetarian Taco Pasta | Vegetarian Taco Pasta | Vegetarian Taco Pasta | Vegetarian Taco Pasta | Vegetarian Taco Pasta |

| 12 | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce[veg 1] | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce |

| 13 | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini | Cheese Tortellini |

| 14 | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine |

| 15 | Maple Sausage | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Mexican Style Chicken Stew |

| 16 | Pork Rib | Chicken Burrito Bowl | Chicken Burrito Bowl | Chicken Burrito Bowl | Chicken Burrito Bowl |

| 17 | Mexican Style Chicken Stew | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage | Maple Sausage |

| 18 | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli | Beef Ravioli |

| 19 | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty |

| 20 | Hash Brown Potatoes w/ Bacon | Hash Brown Potatoes w/ Bacon | Hash Brown Potatoes w/ Bacon | Hash Brown Potatoes w/ Bacon | Italian Sausage w/ Vegetables |

| 21 | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna | Lemon Pepper Tuna |

| 22 | Asian Style Beef Strips w/ Vegetables | Asian Style Beef Strips w/ Vegetables | Asian Style Beef Strips w/ Vegetables | Beef Goulash | Beef Goulash |

| 23 | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Chicken Pesto Pasta | Pepperoni Pizza Slice | Pepperoni Pizza Slice | Pepperoni Pizza Slice |

| 24 | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans | Southwest Beef and Black Beans |

| Menu 2021 | |

|---|---|

| # | MRE XLI (2021) |

| 1 | Chili w/ Beans |

| 2 | Shredded BBQ Beef |

| 3 | Chicken w/ Egg Noodles & Vegetables |

| 4 | Spaghetti w/ Meat Sauce |

| 5 | Chicken Chunks |

| 6 | Beef Taco |

| 7 | Beef Brisket |

| 8 | Meatballs w/ Marinara Sauce |

| 9 | Beef Stew |

| 10 | Chili and Macaroni |

| 11 | Vegetarian Taco Pasta |

| 12 | Elbow Macaroni and Tomato Sauce |

| 13 | Cheese Tortellini |

| 14 | Spinach Mushrooms & Cream Sauce Fettuccine |

| 15 | Mexican Style Chicken Stew |

| 16 | Chicken Burrito Bowl |

| 17 | Maple Sausage |

| 18 | Beef Ravioli |

| 19 | Jalapeno Pepper Jack Beef Patty |

| 20 | Italian Sausage w/ Vegetables |

| 21 | Lemon Pepper Tuna |

| 22 | Beef Goulash |

| 23 | Pepperoni Pizza Slice |

| 24 | Southwest Beef and Black Beans |

Date codes

The cases of MREs and their variants usually are marked with the production date in the American fashion: 2-digit Month / 2-digit Day / 4-digit Year (e.g., November 24, 1996 would be rendered as 11/24/1996). This is followed by the Lot Number, a 4-digit Julian date code that is also repeated on the individual components in the MREs. The first digit is the last digit of the Year (e.g., 0 could be equal to 2010 or 2020, 1 could be equal to 2001 or 2011, and 9 could be equal to 2009 or 2019). The next 3 digits are equal to the day of the year (i.e., 001 to 366). "1068" could be equal to the 68th day of 2001 or 2011, for example March 9, 2001.[31] "2068" could mean March 8, 2012 or March 9, 2022 (the 68th day of 2012 is March 8 due to the presence of a leap day).

The cases are also stamped with the Inspection / Test Date, which is in the same format as the Packing Date (e.g., October 1994 would be rendered as "10/94"). Rations optimally must be kept in a cool, dry place during storage. If the rations are stored at 80° for 3 consecutive years, they would reach the end of their shelf life. They are often inspected by the U.S. Army veterinary food personnel and their shelf life may extend beyond the inspection test date.[32] Rations are discarded after five years.[citation needed]

Civilian use

MREs have also been distributed to civilians during natural disasters.[1] The National Guard has provided MREs to the public during national disasters, such as Hurricanes Katrina, Ike, Maria and Sandy; and the 2011 Super Outbreak. The large number of civilians exposed to MREs prompted several jokes during the recent New Orleans Mardi Gras, with revellers donning clothing made of MRE packets with phrases such as "MRE Antoinette" (referring to Marie Antoinette; the wife of King Louis XVI) and "Man Ready to Eat."[citation needed]

The use of rations for noncombat environments has been questioned.[13] While the nutritional requirements are suitable for a combat environment where servicemembers will burn many calories and lose much sodium through sweat, it has been provided as emergency food or even as a standard meal.[33] The high-fat (averaging about 52 grams of fat, 5 grams trans fats)[citation needed] and high-salt content (averaging about 2 grams)[33] are less than ideal for sedentary situations. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, a 77-year-old civilian man with prior congestive heart failure ended up with volume overload from the high sodium content of MREs.[33] The HDR and TOTM account for this nutritional need.[citation needed]

Criticisms

Some of the early MRE main courses were not very palatable, earning them the nicknames "Meals Rejected by Everyone",[34] "Meals Rejected by Ethiopians" (during the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia), or "Meals Rarely Edible".[35] Some individual portions had their own nicknames. For example, the frankfurters, which came sealed in pouches of four, were referred to as "the four fingers of death".[34] Although quality has improved over the years, many of the nicknames have stuck. MREs were sometimes called "Three Lies for the Price of One ... it's not a Meal, it's not Ready, and you can't Eat it."[36] As late as the 2010 deployment to Afghanistan, one veteran in November 2019 characterized MREs (the traditional Thanksgiving meal had been destroyed in an attack, and the standard MRE shipment partially destroyed) as "accursed things".[37]

Their low dietary fiber content could cause constipation in some, so they were also known as "Meals Requiring Enemas", "Meals Refusing to Exit",[38][39] "Meals Refusing to Excrete", or "Massive Rectal Expulsions". While the laxative effect of xylitol sweetener (if excessively consumed) may contribute to a myth that the gum found in MREs contains a laxative, the crackers in the ration pack do contain a higher-than-normal vegetable content to facilitate digestion. In December 2006, comedian Al Franken (on his eighth United Service Organizations tour at the time) joked to troops in Iraq that he had his fifth MRE so far and "none of them had an exit strategy."[40] By 2015, the average fiber content per pack of MRE has improved to an adequate 12 grams.[14]

A superstition exists among troops about the Charms candies that come with some menus: they are considered bad luck, especially if actually eaten.[41][42]

In March 2007, The Salt Lake Tribune invited three gourmet chefs to taste-test 18 MRE meals. None of the meals rated higher than a 5.7 average on a scale of 1-to-10, and the chicken fajita meal in particular was singled out for disdain, rating an average score of 1.3.[43][44] In 2010, the New York Times reported that a French combat ration (such as cassoulet with accompaniments of deer pâté and nougat) could be traded for around five MREs,[42] though by 2014 it was claimed that MRE menus had improved to the point that their worth had reversed.[45]

The vegetable cheese omelet MRE, Recipe No. 4, introduced in 2005, is generally considered the worst ever. Soldiers serving in Iraq dubbed it the "Vomelet" (a pun with vomit), both for its appearance and taste. It was discontinued in 2009.[46]

Variants and similar rations

The MRE has led to the creation of several similar field rations. Aircrew Build to Order Meal Module (ABOMM) are a special variant consisting of repacking existing MRE food elements into a form that provides military flight crews and tank operators with a meal designed to be eaten on the go or while operating their aircraft or ground vehicle without the use of utensils, and packaged for use in confined spaces.[47]

Meal, Religious, Kosher/Halal

For servicemembers with strict religious dietary requirements, the military offers the specialized Meal, Religious, Kosher/Halal.[48] These are tailored to provide the same nutritional content, but will not contain offending ingredients.[49] The entrees come in distinct stylized packaging with a color picture of the prepared entree on it (like civilian pre-made meals) and the food accessories come in commercial packaging. Kosher entrees are marked "Glatt Kosher" in Hebrew and English, while halal entrees are marked "Dhabiha Halal" in Arabic and English. The meals come in cases of 12 that weigh 18 lbs (8 kg) and have a volume of 1.4 cubic feet (40 L). To keep with dietary laws, the entree and accessory packets are packed in two separate inner boxes in an outer case and come in kosher or halal only (the two special ration types are never mixed in a shipping case).

The original meals were kosher only and came in 4 Beef, 4 Chicken, 2 Salmon, and 2 Gefilte Fish menus. The meals now come in Beef, Lamb, Chicken, Vegetarian, and Pasta dishes. The entrees are a mixture of traditional Middle-Eastern and Southwest-Asian dishes (like Lamb & Vegetable Jalfrezi or Curried Chicken with Basmati Rice, Lentils, and Vegetables) and Western dishes (like Vegetable Ratatouille, Florentine-style Vegetable Lasagna, or New Orleans Gumbo with Chicken). Each menu contains an average of 1200 kilocalories and has a shelf life of 3 to 10 months.

There is also a special kosher meal certified for Passover requirements.[50] The "Passover Ration" (officially called the Meal, Religious, Kosher for Passover) contains packages of Matzoh crackers and has beef, chicken (served on the bone), or salmon entrees. Each meal is in its own packet and come 12 packets to a case.

For less strictly-observing servicemembers, non-certified "pork-free" menus of the regular MRE are available. The DLA offers Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE), Pork-Free, Individual, which consist of 12 menus selected from the regular roster of 24.[51]

Vegetarian HDR and MARC

The Humanitarian Daily Ration (HDR) is a self-contained Halal meal designed to be given to refugees and other displaced people. It is designed to feed a person for a full day, and the menus are intended to be palatable to many religious and cultural tastes. To meet this goal, no animal products or by-products, no alcohol or alcohol-based products, and minimal dairy products are used in their production. It is otherwise created and packaged much like MREs; feedback from the Afghanistan campaign led to the interior packing being reinforced to withstand being air-dropped, as the packets sometimes ruptured on impact. The outer bag is tinted a high-visibility red or yellow and has an American flag and a picture of a person eating out of the bag with a spoon. There are usually instructions printed on it in English and one or more local languages as well.

The Meal, Alternative Regionally Customized (MARC) is a self-contained, shelf-stable meal developed by U.S. Army Soldier and Biological Chemical Command (SBCCOM)/Natick, Individual Combat Ration Team (ICRT), Combat Feeding Directorate (CFD). MARCs were developed specifically for detainees at Guantanamo Bay, and have since found wider spread use, notably Iraq and Afghanistan. MARC meals are entirely vegetarian as an easy way to prevent conflicts with culturally "prohibited products" (Islam and Judaism forbidding pork, Hindus avoiding beef, etc). They are neither Kosher nor Halal certified. Many of the menus available have a Southeast Asian or Indian style to them (Saag Chole, curried vegetables), but others are simply the equivalent of vegetarian MREs (Cheese Tortellini, Minestrone).[52]

Higher-calorie variants

In extreme cold temperatures, the packaged wet food in MREs can freeze solid, rendering the food inedible and the heating packet insufficient. The Meal, Cold Weather (MCW) provides a ration similar to the MRE designed for lower temperatures than the MRE can withstand. Clad in white packaging, it offers a freeze-dried entree designed to be eaten with heated water, the same side ingredients as the standard MRE, and additional drink mixes to encourage additional hydration. The caloric and fat content of the meals is also increased.[53] The MCW replaced the Ration, Cold Weather (RCW).[54]

The Meal, Long Range Patrol (LRP) is essentially the same as the MCW, but with different accessory packs. The MLRP is designed for troops who may receive limited or no supply, and weight of the ration is critical.[53] The similar First Strike Ration is along the same lines, but requires no preparation and may be eaten on the go.

Special requirement food

The Modular Operational Rations Enhancement (MORE) is issued as a supplement to meals for troops in extreme, demanding operational environments such as high-intensity training events.[55][56]

The Tailored Operational Training Meal (TOTM) first entered service in May 2001. It provides a lower calorie count (an average of 997 kilocalories) for less intensive training environments, such as classroom instruction. It replaces the earlier mess-hall bagged lunches, catered meals or field kitchens for field instruction. The TOTM allows troops to become familiar with the MRE and its contents without providing an excessive amount of calories to troops who will not necessarily burn them. It uses a transparent outer plastic bag with commercial markings rather than the MRE's tan plastic bag with standard markings. There are currently 3 different lists of twelve menus, making a total of 36 different meals. Each TOTM ration case is packed with a full menu of 12 assorted meals, weighs about 20 lbs (9 kg), and is 0.95 cubic feet (27 L). The TOTM has a more limited shelf-life than the MRE, with a duration of only 12 to 18 months.[57]

The Unitized Group Ration (UGR) is a ration much like the MRE, but expanded to feed large groups. It is the successor to the older A-ration, B-ration, and T-ration It comes packed in sealed metal trays that are heated and then opened.

The Food Packet, Survival, General Purpose, Improved (FPSGPI) is given to pilots and other servicemembers that may require a small, extremely portable food ration for emergencies. It contains food bars and a drink mix.[58] Similarly, the Food Packet, Survival, Abandon Ship (FPSAS) and Food Packet, Survival, Aircraft, Life Raft (FPSALR) are fitted into the storage areas on lifeboats.[59][60]

The "Jimmy Dean," a pre-packaged shelf-stable ration containing, among other items, a pre-made Jimmy Dean brand deli-style sandwich, is often issued in the field to U.S. servicemen as an alternative to MREs.[61]

Ratfucking

The term ratfucking (rat in this case is shorthand for ration) is a slang term used by U.S. military personnel to describe the targeted pillaging of MREs, which the military officially calls "field stripping". It refers to the process of opening a case of MREs (which are packed 12 in a box), opening up individual MRE packages, removing the desired items, and leaving the unenticing remainder.[62]

See also

Lua error: bad argument #2 to 'title.new' (unrecognized namespace name 'Portal').

- Airline meal

- Camping food

- Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center – prime developer of the MRE

- Military chocolate (United States)

- Individual Meal Pack – Canadian equivalent to the MRE

- Ninja diet

- List of military food topics

- Space food

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/rdr/teaching/acc-risk-disaster-reduction/mres[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Mason, V.C., Meyer, A.V., and Klicka, M.V., Summary of Operational Rations, Natick, MA: U.S. Army Natick Research & Development Laboratory Technical Report TR-82/013 (June 1982): The MRE was officially type-classified for adoption in 1975 but due to budget cuts was not officially placed into production until 1981; stocks of the MCI continued to be issued until exhausted.

- ↑ General Orders, 8 August 1775 |access-date=March 2022 | url = https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0173

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kearny, Cresson H. (Major), Jungle Snafus ... And Remedies, Oregon Institute (1996), pp. 286–291

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Institute of Medicine, Dietary Reference Intake

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).[permanent dead link]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Optimization of Nutrient Composition of Military Rations for Short-Term, High-Stress Situations, Nutrient composition of rations for short-term, high-intensity combat operations pp. 15–27

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

Further reading

- Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

External links

- Operational Rations of the Department of Defense, 9th Edition

- How MREs Work

- NPR All Things Considered, mentions the new MRE menu for 2004 (at 5 minutes 02 seconds)

- Military Packages Put Technology to the Test

- MRE taste test: Airman staff goes tactical to spill the beans on meals, ready to eat

- Military buys special meals for Jewish, Muslim troops Archived 2020-08-04 at the Wayback Machine

- MREInfo.com – Complete source of information on MREs both in US and International

- Ready To Eat! 30 Years of the MRE

- The Eat of Battle – how the World's Armies get fed

- How long do MRES last