The scissors are a series of turn reversals and flight path overshoots intended to slow the relative forward motion (downrange travel) of the aircraft in an attempt to either force a dangerous overshoot, on the part of the defender, or prevent a dangerous overshoot on the attacker's part. The defender's goal is to stay out of phase with the attacker, trying to prevent a guns solution, while the attacker tries to get in phase with the defender. The advantage usually goes to the more maneuverable aircraft. There are two types of scissor maneuvers, called flat scissors and rolling scissors.[1]

Flat scissors

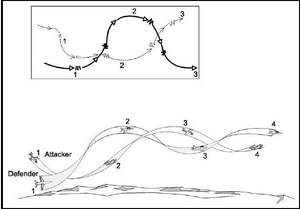

Flat scissors, also called horizontal scissors, usually occur after a low-speed overshoot in a horizontal direction. The defender reverses the turn, attempting to force the attacker to fly out in front and to spoil aim. The attacker then reverses, trying to remain behind the defender, and the two aircraft begin a weaving flight pattern.[2]

Offensive maneuvering in a Flat Scissors

The goal of the offensive aircraft in a flat scissors is to shoot the bogey. To do this the offensive aircraft must maneuver to get in-phase with the bogey in order to bring their guns to bear. This will be accomplished by early turning the bogey as it approaches your canopy aft bow.[2]

Defensive maneuvering in a Flat Scissors

The goal of the defensive aircraft in a flat scissors is not to be shot. To do this the defender will attempt to keep the attacker out-of-phase (such that a guns solution is not possible). As the attacker crosses your extended six, the defender will reverse its turn to stay out-of-phase and attempt to neutralize the fight. During the flat scissors demonstration, the IPs will conduct a role reversal such that both students will have the opportunity to see the maneuver from both an offensive and defensive perspective.[2]

Rolling scissors

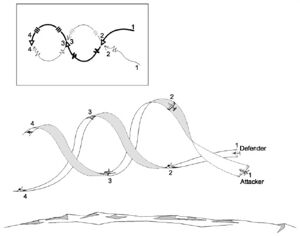

Rolling scissors, also called vertical scissors, tend to happen after a high-speed overshoot from above. The defender reverses into a vertical climb and into a barrel roll over the top, forcing the attacker to attempt to follow. The advantage lies in the aircraft that can pull its nose through the top or bottom of the turn faster. In battles with aircraft that have a thrust-to-weight ratio of less than one the aircraft will quickly lose altitude, and crashing into the ground becomes a possibility.[3] According to author Mike Spick, "Disengagement from a vertical rolling scissors is best made with a split-s and a lot of hope."[4]

A developed rolling scissors maneuver involves a series of horizontal and vertical overshoots. The maneuver aims to gain a positional advantage by reducing downrange travel relative to the opponent. The defender initiates the maneuver by declaring "Fight's on," followed by the attacker echoing the same phrase and executing a standard roll-in off the perch and low reversal. The attacker continues the attack with an in-close flight path overshoot, which the defender takes advantage of by performing a reversing pull into the vertical.

The defender utilizes available energy to reverse over the top, rolling about the flight path of the attacker. The objective is to execute the scissors perfectly and capitalize on any mistakes made by the opponent. Three-dimensional maneuvering is employed to effectively control energy, including pulling up wings level into the vertical, making heading changes by rolling off after reaching the desired vertical altitude, trading airspeed for altitude to reduce the forward vector, and properly controlling angle of attack.

The main goal is to stay behind the opponent. The key to winning the rolling scissors is the ability to raise the nose when at the bottom of a roller before the opponent can lower their nose when at the top, and vice versa. This strategy, known as the tactical egg, allows for gradual positional advantage over time, provided energy and position are not sacrificed.

The saying "lag at the bottom and lead over the top" refers more to stick and rudder skills rather than a geometric analysis of winning a rolling scissors. The actual strategy involves establishing the highest reasonable nose attitude, getting the nose down before the opponent can raise theirs (early turn), and lagging them down the backside to gain turning room and a 3-9 advantage. This ensures that the opponent travels further downrange. The lift vector placement is crucial, as incorrect positioning can lead to flying ahead of the opponent.

During the backside of the roller, lag pursuit slows downrange travel, allowing for a brief opportunity to unload and regain energy. It is important to have sufficient energy, around 180 KIAS at about 90 degrees nose down, for the wings level pull-up to start again. The objective is to capitalize on an overshoot by establishing the highest nose attitude and utilizing an early turn over the top, which forces the opponent to pitch shallower and travel further downrange. The defender repeats the cycle, gradually wearing down the opponent.

Typically, an aircraft feels offensive at the top of a roller and defensive at the bottom, although this perception may be influenced by radial G and the tactical egg. If the opponent is predominantly in the forward part of the canopy, the defender is considered offensive and vice versa.

In certain aircraft like the T-2C, which has a thrust-to-weight ratio of less than 1, the rolling scissors tends to be a downhill fight, resulting in lower peak altitudes with each revolution. Monitoring airspeed and altitude at the top and bottom of the roller is crucial. Deck awareness is essential as the T-2C requires approximately 3000 feet above the hard deck to continue a roller from its apex. It is important not to jeopardize the fight by getting too close to the hard deck. As the fight deteriorates, it often transitions into a horizontal scissors maneuver.[3]

- ↑ Scissors Maneuvering Archived June 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Flight Training Instruction

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Figure 10-18 Flat Scissors, Flight Training Instruction

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Basic Fighter Maneuvers Chapter 10.

- ↑ Spick, Mick (1987). An illustrated guide to modern fighter combat. London: Salamander. p. 147