Appendix. The Means of Acquiring A Good Strategic Coup-d'Oeil.

Summary

Full Text

Mendell and Craighill Translation[1]

The study of the principles of strategy can produce no valuable practical results if we do nothing more than keep them in remembrance, never trying to apply them, with map in hand, to hypothetical wars, or to the brilliant operations of great captains. By such exercises may be procured a rapid and certain strategic coup-d'oeil,—the most valuable characteristic of a good general, without which he can never put in practice the finest theories in the world.

When a military man who is a student of his art has become fully impressed by the advantages procured by moving a strong mass against successive fractions of the enemy's force, and particularly when he recognizes the importance of constantly directing the main efforts upon decisive points of the theater of operations, he will naturally desire to be able to perceive at a glance what are these decisive points. I have already, in Chapter III., page 70, of the preceding Summary, indicated the simple means by which this knowledge may be obtained. There is, in fact, one truth of remarkable simplicity which obtains in all the combinations of a methodical war. It is this:—in every position a general may occupy, he has only to decide whether to operate by the right, by the left, or by the front.

To be convinced of the correctness of this assertion, let us first take this general in his private office at the opening of the war. His first care will be to choose that zone of operations which will give him the greatest number of chances of success and be the least dangerous for him in case of reverse. As no theater of operations can have more than three zones, (that of the right, that of the center, and that of the left,) and as I have in Articles from XVII. to XXII. pointed out the manner of perceiving the advantages and dangers of these zones, the choice of a zone of operations will be a matter of no difficulty.

When the general has finally chosen a zone within which to operate with the principal portion of his forces, and when these forces shall be established in that zone, the army will have a front of operations toward the hostile army, which will also have one. Now, these fronts of operations will each have its right, left, and center. It only remains, then, for the general to decide upon which of these directions he can injure the enemy most,—for this will always be the best, especially if he can move upon it without endangering his own communications. I have dwelt upon this point also in the preceding Summary.

Finally, when the two armies are in presence of each other upon the field of battle where the decisive collision is to ensue, and are upon the point of coming to blows, they will each have a right, left, and center; and it remains for the general to decide still between these three directions of striking.

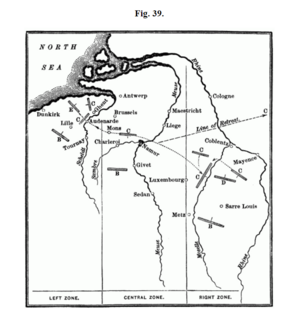

Let us take, as an illustration of the truths I have mentioned, the theater of operations, already referred to, between the Rhine and the North Sea. (See Fig. 39.)

Although this theater presents, in one point of view, four geographical sections,—viz.: the space between the Rhine and the Moselle, that between the Moselle and the Meuse, that between the Meuse and the Scheldt, and that between the last river and the sea,—it is nevertheless true that an army of which A A is the base and B B the front of operations will have only three general directions to choose from; for the two spaces in the center will form a single central zone, as [Pg 339]it will always have one on the right and another on the left.

The army B B, wishing to take the offensive against the army CC, whose base was the Rhine, would have three directions in which to operate. If it maneuvered by the extreme right, descending the Moselle, (toward D,) it would evidently threaten the enemy's line of retreat toward the Rhine; but he, concentrating the mass of his forces toward Luxembourg, might fall upon the left of the army D and compel it to change front and fight a battle with its rear toward the Rhine, causing its ruin if seriously defeated.

[Pg 340]If, on the contrary, the army B wished to make its greatest effort upon the left, (toward E,) in order to take advantage of the finely-fortified towns of Lille and Valenciennes, it would be exposed to inconveniences still more serious than before. For the army CC, concentrating in force toward Audenarde, might fall on the right of B, and, outflanking this wing in the battle, might throw it upon the impassable country toward Antwerp between the Scheldt and the sea,—where there would remain but two things for it to do: either to surrender at discretion, or cut its way through the enemy at the sacrifice of half its numbers.

It appears evident, therefore, that the left zone would be the most disadvantageous for army B, and the right zone would be inconvenient, although somewhat favorable in a certain point of view. The central zone remains to be examined. This is found to possess all desirable advantages, because the army B might move the mass of its force toward Charleroi with a view of cutting through the immense front of operations of the enemy, might overwhelm his center, and drive the right back upon Antwerp and the Lower Scheldt, without seriously exposing its own communications.

When the forces are chiefly concentrated upon the most favorable zone, they should, of course, have that direction of movement toward the enemy's front of operations which is in harmony with the chief object in view. For example, if you shall have operated by your right against the enemy's left, with the intention of cutting off the greater portion of his army from its base of the Rhine, you should certainly continue to operate in the same direction; for if you should make your greatest effort against the right of the enemy's front, while your plan was to gain an advantage over his left, your operations could not result as you anticipated, no matter how well they might be executed. If, on the contrary, you had decided to take the left zone, with the intention of crowding the enemy back upon the sea, you ought constantly to maneuver by your right in order to accomplish your object; for if you maneuvered by the left, yourself and not the enemy would be the party thrown back upon the sea in case of a reverse.

[Pg 341]Applying these ideas to the theaters of the campaigns of Marengo, Ulm, and Jena, we find the same three zones, with this difference, that in those campaigns the central direction was not the best. In 1800, the direction of the left led straight to the left bank of the Po, on the line of retreat of Mélas; in 1805, the left zone was the one which led by the way of Donauwerth to the extreme right, and the line of retreat of Mack; in 1806, however, Napoleon could reach the Prussian line of retreat by the right zone, filing off from Bamberg toward Gera.

In 1800, Napoleon had to choose between a line of operations on the right, leading to the sea-shore toward Nice and Savona, that of the center, leading by Mont-Cenis toward Turin, and that of the left, leading to the line of communications of Mélas, by way of Saint-Bernard or the Simplon. The first two directions had nothing in their favor, and the right might have been very dangerous,—as, in fact, it proved to Massena, who was forced back to Genoa and there besieged. The decisive direction was evidently that by the left.

I have said enough to explain my ideas on this point.

The subject of battles is somewhat more complicated; for in the arrangements for these there are both strategical and tactical considerations to be taken into account and harmonized. A position for battle, being necessarily connected with the line of retreat and the base of operations, must have a well-defined strategic direction; but this direction must also depend somewhat upon the character of the ground and the stations of the troops of both parties to the engagement: these are tactical considerations. Although an army usually takes such a position for a battle as will keep its line of retreat behind it, sometimes it is obliged to assume a position parallel to this line. In such a case it is evident that if you fall with overwhelming force upon the wing nearest the line of retreat, the enemy may be cut off or destroyed, or, at least, have no other chance of escape than in forcing his way through your line.

I will here mention as illustrations the celebrated battle of [Pg 342]Leuthen in 1757, of which I have given an account in the history of Frederick's wars, and the famous days of Krasnoi, in the retreat from Moscow in 1812.

The annexed figure (40) explains the combination at Krasnoi. The line A A is Napoleon's line of retreat toward C. He took the position B B to cover his line. It is evident that the principal mass of Koutousoff's army D D should have moved to E E in order to fall on the right of the French, whose army would have been certainly destroyed if it had been anticipated at C; for everybody knows in what a state it was while thus fifteen hundred miles from its true base.

There was the same combination at Jemmapes, where Dumouriez, by outflanking the Austrian left, instead of attacking their right, would have entirely cut them off from the Rhine.

At the battle of Leuthen Frederick overwhelmed the Austrian left, which was in the direction of their line of retreat; and for this reason the right wing was obliged to take refuge in Breslau, where it capitulated a few days later.

In such cases there is no cause for hesitation. The decisive point is that wing of the enemy which is nearest his line of retreat, and this line you must seize while protecting your own.

When an enemy has one or two lines of retreat perpendicular to and behind his position of battle, it will generally be best to attack the center, or that wing where the obstacles of the ground shall be the least favorable for the defense; for in such a case the first consideration is to gain the battle, without having in view the total destruction of the enemy. That depends upon the relative numerical strength, the morale of [Pg 343]the two armies, and other circumstances, with reference to which no fixed rules can be laid down.

Finally, it happens sometimes that an army succeeds in seizing the enemy's line of retreat before fighting a battle, as Napoleon did at Marengo, Ulm, and Jena. The decisive point having in such case been secured by skillful marches before fighting, it only remains to prevent the enemy from forcing his way through your line. You can do nothing better than fight a parallel battle, as there is no reason for maneuvering against one wing more than the other. But for the enemy who is thus cut off the case is very different. He should certainly strike most heavily in the direction of that wing where he can hope most speedily to regain his proper line of retreat; and if he throws the mass of his forces there, he may save at least a large portion of them. All that he has to do is to determine whether this decisive effort shall be toward the right or the left.

It is proper for me to remark that the passage of a great river in the presence of a hostile army is sometimes an exceptional case to which the general rules will not apply. In these operations, which are of an exceedingly delicate character, the essential thing is to keep the bridges safe. If, after effecting the passage, a general should throw the mass of his forces toward the right or the left with a view of taking possession of some decisive point, or of driving his enemy back upon the river, whilst the latter was collecting all his forces in another direction to seize the bridges, the former army might be in a very critical condition in case of a reverse befalling it. The battle of Wagram is an excellent example in point,—as good, indeed, as could be desired. I have treated this subject in Article XXXVII., (pages 224 and following.)

A military man who clearly perceives the importance of the truths that have been stated will succeed in acquiring a rapid and accurate coup-d'oeil. It will be admitted, moreover, that a general who estimates them at their true value, and accustoms himself to their use, either in reading military history, or in hypothetical cases on maps, will seldom be in [Pg 344]doubt, in real campaigns, what he ought to do; and even when his enemy attempts sudden and unexpected movements, he will always be ready with suitable measures for counteracting them, by constantly bearing in mind the few simple fundamental principles which should regulate all the operations of war.

Heaven forbid that I should pretend to lessen the dignity of the sublime art of war by reducing it to such simple elements! I appreciate thoroughly the difference between the directing principles of combinations arranged in the quiet of the closet, and that special talent which is indispensable to the individual who has, amidst the noise and confusion of battle, to keep a hundred thousand men co-operating toward the attainment of one single object. I know well what should be the character and talents of the general who has to make such masses move as one man, to engage them at the proper point simultaneously and at the proper moment, to keep them supplied with arms, provisions, clothing, and munitions. Still, although this special talent, to which I have referred, is indispensable, it must be granted that the ability to give wise direction to masses upon the best strategic points of a theater of operations is the most sublime characteristic of a great captain. How many brave armies, under the command of leaders who were also brave and possessed executive ability, have lost not only battles, but even empires, because they were moved imprudently in one direction when they should have gone in the other! Numerous examples might be mentioned; but I will refer only to Ligny, Waterloo, Bautzen, Dennewitz, Leuthen.

I will say no more; for I could only repeat what has already been said. To relieve myself in advance of the blame which will be ascribed to me for attaching too much importance to the application of the few maxims laid down in my writings, I will repeat what I was the first to announce:—"that war is not an exact science, but a drama full of passion; that the moral qualities, the talents, the executive foresight and ability, the greatness of character, of the leaders, and the impulses, sympathies, and passions of the masses, have a great influence [Pg 345]upon it." I may be permitted also, after having written the detailed history of thirty campaigns and assisted in person in twelve of the most celebrated of them, to declare that I have not found a single case where these principles, correctly applied, did not lead to success.

As to the special executive ability and the well-balanced penetrating mind which distinguish the practical man from the one who knows only what others teach him, I confess that no book can introduce those things into a head where the germ does not previously exist by nature. I have seen many generals—marshals, even—attain a certain degree of reputation by talking largely of principles which they conceived incorrectly in theory and could not apply at all. I have seen these men intrusted with the supreme command of armies, and make the most extravagant plans, because they were totally deficient in good judgment and were filled with inordinate self-conceit. My works are not intended for such misguided persons as these, but my desire has been to facilitate the study of the art of war for careful, inquiring minds, by pointing out directing principles. Taking this view, I claim credit for having rendered valuable service to those officers who are really desirous of gaining distinction in the profession of arms.

Finally, I will conclude this short summary with one last truth:—

"The first of all the requisites for a man's success as a leader is, that he be perfectly brave. When a general is animated by a truly martial spirit and can communicate it to his soldiers, he may commit faults, but he will gain victories and secure deserved laurels."