Table of contents -- Chapter VII

Article XLIII. Posting Troops in Line of Battle.

Summary

Full Text

Mendell and Craighill Translation[1]

Having explained in Article XXX. what is to be understood by the term line of battle, it is proper to add in what manner it is to be formed, and how the different troops are to be distributed in it.

Before the French Revolution, all the infantry, formed in regiments and brigades, was collected in a single battle-corps, drawn up in two lines, each of which had a right and a left wing. The cavalry was usually placed upon the wings, and the artillery—which at this period was very unwieldy—was distributed along the front of each line. The army camped together, marching by lines or by wings; and, as there were two cavalry wings and two infantry wings, if the march was by wings four columns were thus formed. When they marched by lines, (which was specially applicable to flank movements,) two columns were formed, unless, on account of local circumstances, the cavalry or a part of the infantry had camped in a third line,—which was rare.

This method simplified logistics very much, since it was only necessary to give such orders as the following:—"The army will move in such direction, by lines or by wings, by the right or by the left." This monotonous but simple forma[Pg 278]tion was seldom deviated from; and no better could have been devised as war was carried on in those days.

The French attempted something new at Minden, by forming as many columns as brigades, and opening roads to bring them to the front in line,—a simple impossibility.

If the labor of staff officers was diminished by this method of camping and marching by lines, it must be evident that if such a system were applied to an army of one hundred thousand or one hundred and fifty thousand men, there would be no end to the columns, and the result would be the frequent occurrence of routs like that of Rossbach.

The French Revolution introduced the system of divisions, which broke up the excessive compactness of the old formation, and brought upon the field fractions capable of independent movement on any kind of ground. This change was a real improvement,—although they went from one extreme to the other, by returning nearly to the legionary formation of the Romans. These divisions, composed usually of infantry, artillery, and cavalry, maneuvered and fought separately. They were very much extended, either to enable them to subsist without the use of depots, or with an absurd expectation of prolonging the line in order to outflank that of the enemy. The seven or eight divisions of an army were sometimes seen marching on the same number of roads, ten or twelve miles distant from each other; the head-quarters was at the center, with no other support than five or six small regiments of cavalry of three hundred or four hundred men each, so that if the enemy concentrated the mass of his forces against one of these divisions and beat it, the line was pierced, and the general-in-chief, having no disposable infantry reserve, could do nothing but order a retreat to rally his scattered columns.

Bonaparte in his first Italian campaign remedied this difficulty, partly by the mobility of his army and the rapidity of his maneuvers, and partly by concentrating the mass of his divisions upon the point where the decisive blow was to fall. When he became the head of the government, and saw the sphere of his means and his plans constantly increas[Pg 279]ing in magnitude, he readily perceived that a stronger organization was necessary: he avoided the extremes of the old system and the new, while still retaining the advantages of the divisional system. Beginning with the campaign of 1800, he organized corps of two or three divisions, which he placed under the command of lieutenant-generals, and formed of them the wings, the center, and the reserve of his army.[2]

This system was finally developed fully at the camp of Boulogne, where he organized permanent army corps under the command of marshals, who had under their orders three divisions of infantry, one of light cavalry, from thirty-six to forty pieces of cannon, and a number of sappers. Each corps was thus a small army, able at need to act independently as an army. The heavy cavalry was collected in a single strong reserve, composed of two divisions of cuirassiers, four of dragoons, and one of light cavalry. The grenadiers and the guard formed an admirable infantry reserve. At a later period—1812—the cavalry was also organized into corps of three divisions, to give greater unity of action to the constantly-increasing masses of this arm. This organization was as near perfection as possible; and the grand army, that brought about such great results, was the model which all the armies of Europe soon imitated.

Some military men, in their attempts to perfect the art, have recommended that the infantry division, which sometimes has to act independently, should contain three instead of two brigades, because this number will allow one for the center and each wing. This would certainly be an improvement; for if the division contains but two brigades there is an open space left in the center between the brigades on the wings: these brigades, having no common central support, cannot with safety act independently of each other. Besides this, with three brigades in a division, two may be engaged while the third is held in reserve,—a manifest advantage. But, [Pg 280]if thirty brigades formed in ten divisions of three brigades are better than when formed in fifteen divisions of two brigades, it becomes necessary, in order to obtain this perfect divisional organization, to increase the numbers of the infantry by one-third, or to reduce the divisions of the army-corps from three to two,—which last would be a serious disadvantage, because the army-corps is much more frequently called upon to act independently than a division, and the subdivision into three parts is specially best for that.[3]

What is the best organization to be given an army just setting out upon a campaign will for a long time to come be a problem in logistics; because it is extremely difficult to maintain the original organization in the midst of the operations of war, and detachments must be sent out continually.

The history of the grand army of Boulogne, whose organization seemed to leave nothing farther to be desired, proves the assertion just made. The center under Soult, the right under Davoust, the left under Ney, and the reserve under Lannes, formed together a regular and formidable battle-corps of thirteen divisions of infantry, without counting those of the guard and the grenadiers. Besides these, the corps of Bernadotte and Marmont detached to the right, and that of Augereau to the left, were ready for action on the flanks. But after the passage of the Danube at Donauwerth every thing was changed. Ney, at first reinforced to five divisions, was reduced to two; the battle-corps was divided partly to the right and partly to the left, so that this fine arrangement was destroyed.

It will always be difficult to fix upon a stable organization. Events are, however, seldom so complicated as those of 1805; and Moreau's campaign of 1800 proves that the original organ[Pg 281]ization may sometimes be maintained, at least for the mass of the army. With this view, it would seem prudent to organize an army in four parts,—two wings, a center, and a reserve. The composition of these parts may vary with the strength of the army; but in order to retain this organization it becomes necessary to have a certain number of divisions out of the general line in order to furnish the necessary detachments. While these divisions are with the army, they may be attached to that part which is to receive or give the heaviest blows; or they may be employed on the flanks of the main body, or to increase the strength of the reserve. Bach of the four great parts of the army may be a single corps of three or four divisions, or two corps of two divisions each. In this last case there would be seven corps, allowing one for the reserve; but this last corps should contain three divisions, to give a reserve to each wing and to the center.

With seven corps, unless several more are kept out of the general line in order to furnish detachments, it may happen that the extreme corps may be detached, so that each wing might contain but two divisions, and from these a brigade might be occasionally detached to flank the march of the army, leaving but three brigades to a wing. This would be a weak order of battle.

These facts lead me to conclude that an organization of the line of battle in four corps of three divisions of infantry and one of light cavalry, with three or four divisions for detachments, would be more stable than one of seven corps, each of two divisions.

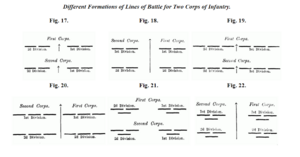

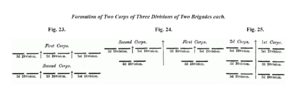

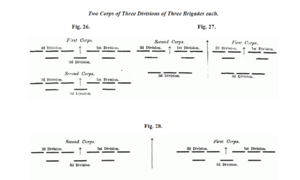

But, as every thing depends upon the strength of the army and of the units of which it is composed, as well as upon the character of the operations in which it may be engaged, the arrangement may be greatly varied. I cannot go into these details, and shall simply exhibit the principal combinations that may result from forming the divisions in two or three brigades and the corps in two or three divisions. I have indicated the formation of two infantry corps in two lines, either one behind the other, or side by side. (See Figures from 17 to 28 inclusive.)

Note.—In all these formations the unit is the brigade in line; but these lines may be formed of deployed battalions, or of battalions in columns of attack by divisions of two companies. The cavalry attached to the corps will be placed on the flanks. The brigades might be so drawn up as to have one regiment in the first line and one in the second.

The question here presents itself, whether it is ever proper to place two corps one behind the other, as Napoleon often did, particularly at Wagram. I think that, except for the reserves, this arrangement may be used only in a position of expectation, and never as an order of battle; for it is much better for each corps to have its own second line and its reserve than to pile up several corps, one behind the other, under different commanders. However much one general may be disposed to support a colleague, he will always object to dividing up his troops for that purpose; and when in the general of the first line he sees not a colleague, but a hated rival, as too frequently happens, it is probable he will be very slow in furnishing the assistance which may be greatly needed. Moreover, a commander whose troops are spread out in a long line cannot execute his maneuvers with near so much facility as if his front was only half as great and was supported by the remainder of his own troops drawn up in rear.

The table below[4] will show that the number of men in an army will have great influence in determining the best formation for it, and that the subject is a complicated one.

In making our calculations, it is scarcely necessary to provide for the case of such immense masses being in the field as were seen from 1812 to 1815, when a single army contained fourteen corps varying in strength from two to five divisions. With such large numbers nothing better can be proposed than a subdivision into corps of three divisions each. Of these corps, eight would form the main body, and there would remain six for detachments and for strengthening any point of the main line that might require support. If this system be applied to an army of one hundred and fifty thousand men, it would be hardly practicable to employ divisions of two brigades each where Napoleon and the allies used corps.

If nine divisions form the main body,—that is, the wings and the center,—and six others form the reserve and detachments, fifteen divisions would be required, or thirty brigades,—which would make one hundred and eighty battalions, if each regiment contains three battalions. This supposition brings our army up to one hundred and forty-five thousand foot-soldiers and two hundred thousand in all. With regiments of two battalions there would be required one hundred and twenty battalions, or ninety-six thousand infantry; but if each regiment contains but two battalions, each battalion should be one thousand men strong, and this would increase the infantry to one hundred and twenty thousand men and the entire army to one hundred and sixty thousand men. These calculations show that the strength of the minor subdivisions must be carefully considered in arranging into corps and divisions. If an army does not contain more than one hundred thousand men, the formation by divisions is perhaps better than by corps. An example of this was Napoleon's army of 1800.

Having now endeavored to explain the best method of giving a somewhat permanent organization to the main body of an army, it will not be out of place for me to inquire whether this permanency is desirable, and if it is not advantageous to deceive the enemy by frequently changing the composition of corps and their positions.

I admit the advantage of thus deceiving the enemy; but it [Pg 287]may be gained while still retaining a quite constant organization of the main body. If the divisions intended for detachments are joined to the wings and the center,—that is, if those parts contain each four divisions instead of three,—and if one or two divisions be occasionally added to the wing which is likely to bear the brunt of an engagement, each wing will be a corps properly of four divisions; but detachments will generally reduce it to three, and sometimes two, while it might, again, be reinforced by a portion of the reserve until it reached five divisions. The enemy would thus never know exactly the strength of the different parts of the line.

But I have dwelt sufficiently on these details. It is probable that, whatever be the strength and number of the subdivisions of an army, the organization into corps will long be retained by all the great powers of Europe, and calculations for the arrangement of the line of battle must be made upon that basis.

The distribution of the troops in the line of battle has changed in recent times, as well as the manner of arranging the line. Formerly it was usually composed of two lines, but now of two lines and one or more reserves. In recent[5] conflicts in Europe, when the masses brought into collision were very large, the corps were not only formed in two lines, but one corps was placed behind another, thus making four lines; and, the reserve being drawn up in the same manner, six lines of infantry were often the result, and several of cavalry. Such a formation may answer well enough as a preparatory one, but is by no means the best for battle, as it is entirely too deep.

The classical formation—if I may employ that term—is still two lines for the infantry. The greater or less extent of the battle-field and the strength of an army may necessarily produce greater depth at times; but these cases are the exceptions, because the formation of two lines and the reserves gives sufficient solidity, and enables a greater number of men to be simultaneously engaged.

When an army has a permanent advanced guard, it may be either formed in front of the line of battle or be carried to [Pg 288]the rear to strengthen the reserve;[6] but, as has been previously stated, this will not often happen with the present method of forming and moving armies. Each wing has usually its own advanced guard, and the advanced guard of the main or central portion of the army is naturally furnished by the leading corps: upon coming into view of the enemy, these advanced bodies return to their proper positions in line of battle. Often the cavalry reserve is almost entirely with the advanced guard; but this does not prevent its taking, when necessary, the place fixed for it in the line of battle by the character of the position or by the wishes of the commanding general.

From what has been stated above, my readers will gather that very great changes of army organization took place from the time of the revival of the art of war and the invention of gunpowder to the French Revolution, and that to have a proper appreciation of the wars of Louis XIV., of Peter the Great, and of Frederick II., they should consider them from the stand-point of those days.

One portion of the old method may still be employed; and if, by way of example, it may not be regarded as a fundamental rule to post the cavalry on the wings, it may still be a very good arrangement for an army of fifty or sixty thousand men, especially when the ground in the center is not so suitable for the evolutions of cavalry as that near the extremities. It is usual to attach one or two brigades of light cavalry to each infantry corps, those of the center being placed in preference to the rear, whilst those of the wings are placed upon the flanks. If the reserves of cavalry are sufficiently numerous to permit the organization of three corps of this arm, giving one as reserve to the center and one to each wing, the arrangement is certainly a good one. If that is impossible, this reserve may be formed in two columns, one on the right of the left wing and the other on the left of the right [Pg 289]wing. These columns may thus readily move to any point of the line that may be threatened.[7]

The artillery of the present day has greater mobility, and may, as formerly, be distributed along the front, that of each division remaining near it. It may be observed, moreover, that, the organization of the artillery having been greatly improved, an advantageous distribution of it may be more readily made; but it is a great mistake to scatter it too much. Few precise rules can be laid down for the proper distribution of artillery. Who, for example, would dare to advise as a rule the filling up of a large gap in a line of battle with one hundred pieces of cannon in a single battery without adequate support, as Napoleon did successfully at Wagram? I do not desire to go here into much detail with reference to the use of this arm, but I will give the following rules:—

1. The horse-artillery should be placed on such ground that it can move freely in every direction.

2. Foot-artillery, on the contrary, and especially that of heavy caliber, will be best posted where protected by ditches or hedges from sudden charges of cavalry. It is hardly necessary for me to add—what every young officer should know already—that too elevated positions are not those to give artillery its greatest effect. Flat or gently-sloping ground is better.

3. The horse-artillery usually maneuvers with the cavalry; but it is well for each army-corps to have its own horse-artillery, to be readily thrown into any desired position. It is, moreover, proper to have horse-artillery in reserve, which may be carried as rapidly as possible to any threatened point. General Benningsen had great cause for self-congratulation at Eylau because he had fifty light guns in reserve; for they had a powerful influence in enabling him to recover himself when his line had been broken through between the center and the left.

4. On the defensive, it is well to place some of the heavy [Pg 290]batteries in front, instead of holding them in reserve, since it is desirable to attack the enemy at the greatest possible distance, with a view of checking his forward movement and causing disorder in his columns.

5. On the defensive, it seems also advisable to have the artillery not in reserve distributed at equal intervals in batteries along the whole line, since it is important to repel the enemy at all points. This must not, however, be regarded as an invariable rule; for the character of the position and the designs of the enemy may oblige the mass of the artillery to move to a wing or to the center.

6. In the offensive, it is equally advantageous to concentrate a very powerful artillery-fire upon a single point where it is desired to make a decisive stroke, with a view of shattering the enemy's line to such a degree that he will be unable to withstand an attack upon which the fate of the battle is to turn. I shall at another place have more to say as to the employment of artillery in battles.

Table of contents -- Chapter VII

- ↑ https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13549/13549-h/13549-h.htm

- ↑ [40] Thus, the army of the Rhine was composed of a right wing of three divisions under Lecourbe, of a center of three divisions under Saint-Cyr, and of a left of two divisions under Saint-Suzanne, the general-in-chief having three divisions more as a reserve under his own immediate orders.

- ↑ [41] Thirty brigades formed in fifteen divisions of two brigades each will have only fifteen brigades in the first line, while the same thirty brigades formed in ten divisions of three brigades each may have twenty brigades in the first line and ten in the second. But it then becomes necessary to diminish the number of divisions and to have but two in a corps,—which would be a faulty arrangement, because the corps is much more likely to be called upon for independent action than the division.

- ↑ [42] Every army has two wings, a center, and a reserve,—in all, four principal subdivisions,—besides accidental detachments. Below are some of the different formations that may be given to infantry. 1st. In regiments of two battalions of eight hundred men each:— Div's. Brig's. Batt'ns. Men. Four corps of two divisions each, and three divisions for detachments 11 = 22 = 88 = 72,000 Four corps of three divisions each, and three divisions for detachments 15 = 30 = 120 = 96,000 Seven corps of two divisions each, and one corps for detachments 16 = 32 = 128 = 103,000 2d. In regiments of three battalions, brigades of six battalions:— Div's. Brig's. Batt'ns. Men. Four corps of two divisions each, besides detachments 11 = 22 = 132 = 105,000 Four corps of three divisions each, besides detachments 15 = 30 = 180 = 144,000 Eight corps of two divisions each 16 = 32 = 192 = 154,000 If to these numbers we add one-fourth for cavalry, artillery, and engineers, the total force for the above formations may be known. It is to be observed that regiments of two battalions if eight hundred men each would become very weak at the end of two or three months' campaigning. If they do not consist of three battalions, then each battalion should contain one thousand men.

- ↑ [43] The term recent here refers to the later wars of Napoleon I.—Translators.

- ↑ [44] As the advanced guard is in presence of the enemy every day, and forms the rear-guard in retreat, it seems but fair at the hour of battle to assign it a position more retired than that in front of the line of battle.

- ↑ [45] This disposition of the cavalry, of course, is made upon the supposition that the ground is favorably situated for it. This is the essential condition of every well-arranged line of battle.