Table of contents -- Chapter III

Article XVIII. Bases of Operations.

Summary

Full Text

Mendell and Craighill Translation[1]

A base of operations is the portion of country from which the army obtains its reinforcements and resources, from which it starts when it takes the offensive, to which it retreats when necessary, and by which it is supported when it takes position to cover the country defensively.

The base of operations is most generally that of supply,—though not necessarily so, at least as far as food is concerned; as, for instance, a French army upon the Elbe might be sub[Pg 78]sisted from Westphalia or Franconia, but its real base would certainly be upon the Rhine.

When a frontier possesses good natural or artificial barriers, it may be alternately either an excellent base for offensive operations, or a line of defense when the state is invaded. In the latter case it will always be prudent to have a second base in rear; for, although an army in its own country will everywhere find a point of support, there is still a vast difference between those parts of the country without military positions and means, as forts, arsenals, and fortified depots, and those other portions where these military resources are found; and these latter alone can be considered as safe bases of operations. An army may have in succession a number of bases: for instance, a French army in Germany will have the Rhine for its first base; it may have others beyond this, wherever it has allies or permanent lines of defense; but if it is driven back across the Rhine it will have for a base either the Meuse or the Moselle: it might have a third upon the Seine, and a fourth upon the Loire.

These successive bases may not be entirely or nearly parallel to the first. On the contrary, a total change of direction may become necessary. A French army repulsed beyond the Rhine might find a good base on Béfort or Besançon, on Mézières or Sedan, as the Russian army after the evacuation of Moscow left the base on the north and east and established itself upon the line of the Oka and the southern provinces. These lateral bases perpendicular to the front of defense are often decisive in preventing the enemy from penetrating to the heart of the country, or at least in rendering it impossible for him to maintain himself there. A base upon a broad and rapid river, both banks being held by strong works, would be as favorable as could be desired.

The more extended the base, the more difficulty will there be in covering it; but it will also be more difficult to cut the army off from it. A state whose capital is too near the frontier cannot have so favorable a base in a defensive war as one whose capital is more retired.

A base, to be perfect, should have two or three fortified points [Pg 79]of sufficient capacity for the establishment of depots of supply. There should be a tête de pont upon each of its unfordable streams.

All are now agreed upon these principles; but upon other points opinions have varied. Some have asserted that a perfect base is one parallel to that of the enemy. My opinion is that bases perpendicular to those of the enemy are more advantageous, particularly such as have two sides almost perpendicular to each other and forming a re-entrant angle, thus affording a double base if required, and which, by giving the control of two sides of the strategic field, assure two lines of retreat widely apart, and facilitate any change of the line of operations which an unforeseen turn of affairs may necessitate.

The quotations which follow are from my treatise on Great Military Operations:—

"The general configuration of the theater of war may also have a great influence upon the direction of the lines of operations, and, consequently, upon the direction of the bases.

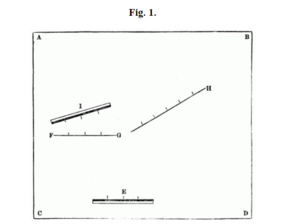

"If every theater of war forms a figure presenting four faces more or less regular, one of the armies, at the opening of the campaign, may hold one of these faces,—perhaps two,—while the enemy occupies the other, the fourth being closed by insurmountable obstacles. The different ways of occupying this theater will lead to widely different combinations. To illustrate, we will cite the theater of the French armies in Westphalia from 1757 to 1762, and that of Napoleon in 1806, both of which are represented in Fig. 1, p. 79. In the first case, the side A B was the North Sea, B D the line of the Weser and the base of Duke Ferdinand, C D the line of the Main and the base of the French army, A C the line of the Rhine, also guarded by French troops. The French held two faces, the North Sea being the third; and hence it was only necessary for them, by maneuvers, to gain the side B D to be masters of the four faces, including the base and the communications of the enemy. The French army, starting from its base C D and gaining the front of operations F G H, could cut off the allied army I from its base B D; the latter would be thrown upon the angle A, formed by the lines of the Rhine, the Ems, and the sea, while the army E could communicate with its bases on the Main and Rhine.

"The movement of Napoleon in 1806 on the Saale was similar. He occupied at Jena and Naumburg the line F G H, then marched by Halle and Dessau to force the Prussian army I upon the sea, represented by the side A B. The result is well known.

"The art, then, of selecting lines of operations is to give them such directions as to seize the communications of the enemy without losing one's own. The line F G H, by its extended position, and the bend on the flank of the enemy, always protects the communications with the base C D; and this is exactly the maneuvers of Marengo, Ulm, and Jena.

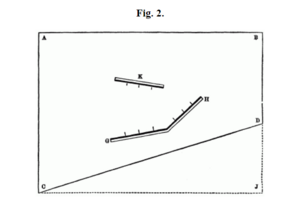

"When the theater of war does not border upon the sea, it is always bounded by a powerful neutral state, which guards its frontiers and closes one side of the square. This may not be an obstacle insurmountable like the sea; but generally it may be considered as an obstacle upon which it would be dangerous to retreat after a defeat: hence it would be an [Pg 81]advantage to force the enemy upon it. The soil of a power which can bring into the field one hundred and fifty or two hundred thousand troops cannot be violated with impunity; and if a defeated army made the attempt, it would be none the less cut off from its base. If the boundary of the theater of war should be the territory of a weak state, it would be absorbed in this theater, and the square would be enlarged till it reached the frontiers of a powerful state, or the sea. The outline of the frontiers may modify the shape of the quadrilateral so as to make it approach the figure of a parallelogram or trapezoid, as in Figure 2. In either case, the advantage of the army which has control of two faces of the figure, and possesses the power of establishing upon them a double base, will be still more decided, since it will be able more easily to cut the enemy off from the shortened side,—as was the case with the Prussian army in 1806, with the side B D J of the parallelogram formed by the lines of the Rhine, the Oder, the North Sea, and the mountainous frontier of Franconia."

The selection of Bohemia as a base in 1813 goes to prove the truth of my opinion; for it was the perpendicularity of this base to that of the French army which enabled the [Pg 82]allies to neutralize the immense advantages which the line of the Elbe would otherwise have afforded Napoleon, and turned the advantages of the campaign in their favor. Likewise, in 1812, by establishing their base perpendicularly upon the Oka and Kalouga, the Russians were able to execute their flank march upon Wiazma and Krasnoi.

If any thing further be required to establish these truths, it will only be necessary to consider that, if the base be perpendicular to that of the enemy, the front of operations will be parallel to his line of operations, and that hence it will be easy to attack his communications and line of retreat.

It has been stated that perpendicular bases are particularly favorable in the case of a double frontier, as in the last figures. Critics may object to this that it does not agree with what is elsewhere said in favor of frontiers which are salient toward the enemy, and against double lines of operations with equality of force. (Art. XXI). The objection is not well founded; for the greatest advantage of a perpendicular base consists in the fact that it forms such a salient, which takes in reverse a portion of the theater of operations. On the other hand, a base with two faces by no means requires that both should be occupied in force: on the contrary, upon one of them it will be sufficient to have some fortified points garrisoned by small bodies, while the great bulk of the force rests upon the other face,—as was done in the campaigns of 1800 and 1806. The angle of nearly ninety degrees formed by the portion of the Rhine from Constance to Basel, and thence to Kehl, gave General Moreau one base parallel and another perpendicular to that of his antagonist. He threw two divisions by his left toward Kehl on the first base, to attract the attention of the enemy to that point, while he moved with nine divisions upon the extremity of the perpendicular face toward Schaffhausen, which carried him in a few days to the gates of Augsburg, the two detached divisions having already rejoined him.

In 1806, Napoleon had also the double base of the Rhine and Main, forming almost a right re-entrant angle. He left Mortier upon the first and parallel one, while with the mass of his forces he gained the extremity of the perpendicular base, and [Pg 83]thus intercepted the Prussians at Gera and Naumburg by reaching their line of retreat.

If so many imposing facts prove that bases with two faces, one of them being almost perpendicular to that of the enemy, are the best, it is well to recollect that, in default of such a base, its advantages may be partially supplied by a change of strategic front, as will be seen in Article XX.

Another very important point in reference to the proper direction of bases relates to those established on the sea-coast. These bases may be favorable in some circumstances, but are equally unfavorable in others, as may be readily seen from what precedes. The danger which must always exist of an army being driven to the sea seems so clear, in the ease of the establishment of the base upon it, (which bases can only be favorable to naval powers,) that it is astonishing to hear in our day praises of such a base. Wellington, coming with a fleet to the relief of Spain and Portugal, could not have secured a better base than that of Lisbon, or rather of the peninsula of Torres-Vedras, which covers all the avenues to that capital on the land side. The sea and the Tagus not only protected both flanks, but secured the safety of his only possible line of retreat, which was upon the fleet.

Blinded by the advantages which the intrenched camp of Torres-Vedras secured for the English, and not tracing effects to their real causes, many generals in other respects wise contend that no bases are good except such as rest on the sea and thus afford the army facilities of supply and refuge with both flanks secured. Fascinated by similar notions, Colonel Carion-Nizas asserted that in 1813 Napoleon ought to have posted half of his army in Bohemia and thrown one hundred and fifty thousand men on the mouths of the Elbe toward Hamburg; forgetting that the first precept for a continental army is to establish its base upon the front farthest from the sea, so as to secure the benefit of all its elements of strength, from which it might find itself cut off if the base were established upon the coast.

An insular and naval power acting on the continent would pursue a diametrically opposite course, but resulting from the [Pg 84]same principle, viz.: to establish the base upon those points where it can be sustained by all the resources of the country, and at the same time insure a safe retreat.

A state powerful both on land and sea, whose squadrons control the sea adjacent to the theater of operations, might well base an army of forty or fifty thousand men upon the coast, as its retreat by sea and its supplies could be well assured; but to establish a continental army of one hundred and fifty thousand men upon such a base, when opposed by a disciplined and nearly equal force, would be an act of madness.

However, as every maxim has its exceptions, there is a case in which it may be admissible to base a continental army upon the sea: it is, when your adversary is not formidable upon land, and when you, being master of the sea, can supply the army with more facility than in the interior. We rarely see these conditions fulfilled: it was so, however, during the Turkish war of 1828 and 1829. The whole attention of the Russians was given to Varna and Bourghas, while Shumla was merely observed; a plan which they could not have pursued in the presence of a European army (even with the control of the sea) without great danger of ruin.

Despite all that has been said by triflers who pretend to decide upon the fate of empires, this war was, in the main, well conducted. The army covered itself by obtaining the fortresses of Brailoff, Varna, and Silistria, and afterward by preparing a depot at Sizeboli. As soon as its base was well established it moved upon Adrianople, which previously would have been madness. Had the season been a couple of months longer, or had the army not come so great a distance in 1828, the war would have terminated with the first campaign.

Besides permanent bases, which are usually established upon our own frontiers, or in the territory of a faithful ally, there are eventual or temporary bases, which result from the operations in the enemy's country; but, as these are rather temporary points of support, they will, to avoid confusion, be discussed in Article XXIII.