| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

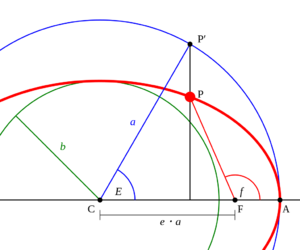

In celestial mechanics, true anomaly is an angular parameter that defines the position of a body moving along a Keplerian orbit. It is the angle between the direction of periapsis and the current position of the body, as seen from the main focus of the ellipse (the point around which the object orbits).

The true anomaly is usually denoted by the Greek letters ν or θ, or the Latin letter f, and is usually restricted to the range 0–360° (0–2πc).

The true anomaly f is one of three angular parameters (anomalies) that defines a position along an orbit, the other two being the eccentric anomaly and the mean anomaly.

Formulas

From state vectors

For elliptic orbits, the true anomaly ν can be calculated from orbital state vectors as:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu = \arccos\left(\frac{e \cdot r}{|e| \cdot |r|}\right)}

- (if r ⋅ v < 0 then replace ν by 2π − ν)

- (if r ⋅ v < 0 then replace ν by 2π − ν)

where:

- v is the orbital velocity vector of the orbiting body,

- e is the eccentricity vector,

- r is the orbital position vector (segment FP in the figure) of the orbiting body.

Circular orbit

For circular orbits the true anomaly is undefined, because circular orbits do not have a uniquely determined periapsis. Instead the argument of latitude u is used:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle u = \arccos { {\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{r}} \over { \mathbf{\left |n \right |} \mathbf{\left |r \right |} }}}

- (if rz < 0 then replace u by 2π − u)

where:

- n is a vector pointing towards the ascending node (i.e. the z-component of n is zero).

- rz is the z-component of the orbital position vector r

Circular orbit with zero inclination

For circular orbits with zero inclination the argument of latitude is also undefined, because there is no uniquely determined line of nodes. One uses the true longitude instead:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle l = \arccos { r_x \over { \mathbf{\left |r \right |}}}}

- (if vx > 0 then replace l by 2π − l)

where:

- rx is the x-component of the orbital position vector r

- vx is the x-component of the orbital velocity vector v.

From the eccentric anomaly

The relation between the true anomaly ν and the eccentric anomaly Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle E} is:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \cos{\nu} = {{\cos{E} - e} \over {1 - e \cos{E}}}}

or using the sine[1] and tangent:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \begin{align} \sin{\nu} &= <nowiki>{{\sqrt{1 - e^2\,} \sin{E}}</nowiki> \over {1 - e \cos{E}}} \\[4pt] <nowiki> </nowiki>\tan{\nu} = <nowiki>{{\sin{\nu}}</nowiki> \over {\cos{\nu}}} &= <nowiki>{{\sqrt{1 - e^2\,} \sin{E}}</nowiki> \over {\cos{E} -e}} \end{align}}

or equivalently:

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \tan{\nu \over 2} = \sqrt{{{1 + e\,} \over {1-e\,}}} \tan{E \over 2}}

so

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu = 2 \, \operatorname{arctan}\left(\, \sqrt{{{1 + e\,} \over {1 - e\,}}} \tan{E \over 2} \, \right)}

Alternatively, a form of this equation was derived by [2] that avoids numerical issues when the arguments are near Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \pm\pi} , as the two tangents become infinite. Additionally, since Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{E}{2}} and Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{\nu}{2}} are always in the same quadrant, there will not be any sign problems.

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \tan{\frac{1}{2}(\nu - E)} = \frac{\beta\sin{E}}{1 - \beta\cos{E}}} where Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \beta = \frac{e}{1 + \sqrt{1 - e^2}} }

so

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu = E + 2\operatorname{arctan}\left(\,\frac{\beta\sin{E}}{1 - \beta\cos{E}}\,\right)}

From the mean anomaly

The true anomaly can be calculated directly from the mean anomaly Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle M} via a Fourier expansion:[3]

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu = M + 2 \sum_{k=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{k} \left[ \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} J_n(-ke)\beta^{|k+n|} \right] \sin{kM}}

with Bessel functions Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle J_n} and parameter Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \beta = \frac{1-\sqrt{1-e^2}}{e}} .

Omitting all terms of order Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle e^4} or higher (indicated by Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \operatorname{\mathcal{O}}\left(e^4\right)} ), it can be written as[3][4][5]

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu = M + \left(2e - \frac{1}{4} e^3\right) \sin{M} + \frac{5}{4} e^2 \sin{2M} + \frac{13}{12} e^3 \sin{3M} + \operatorname{\mathcal{O}}\left(e^4\right).}

Note that for reasons of accuracy this approximation is usually limited to orbits where the eccentricity Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle e} is small.

The expression Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \nu - M} is known as the equation of the center, where more details about the expansion are given.

Radius from true anomaly

The radius (distance between the focus of attraction and the orbiting body) is related to the true anomaly by the formula

- Failed to parse (SVG with PNG fallback (MathML can be enabled via browser plugin): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle r = a\,{1 - e^2 \over 1 + e \cos\nu}\,\!}

where a is the orbit's semi-major axis.

See also

References

- ↑ Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications by David A. Vallado

- ↑ Broucke, R.; Cefola, P. (1973). "A Note on the Relations between True and Eccentric Anomalies in the Two-Body Problem". Celestial Mechanics. 7 (3): 388–389. Bibcode:1973CeMec...7..388B. doi:10.1007/BF01227859. ISSN 0008-8714. S2CID 122878026.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Battin, R.H. (1999). An Introduction to the Mathematics and Methods of Astrodynamics. AIAA Education Series. American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics. p. 212 (Eq. (5.32)). ISBN 978-1-60086-026-3. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ↑ Smart, W. M. (1977). Textbook on Spherical Astronomy (PDF). p. 120 (Eq. (87)). Bibcode:1977tsa..book.....S.

- ↑ Roy, A.E. (2005). Orbital Motion (4 ed.). Bristol, UK; Philadelphia, PA: Institute of Physics (IoP). p. 78 (Eq. (4.65)). Bibcode:2005ormo.book.....R. ISBN 0750310154. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

Further reading

- Murray, C. D. & Dermott, S. F., 1999, Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-57597-4

- Plummer, H. C., 1960, An Introductory Treatise on Dynamical Astronomy, Dover Publications, New York. OCLC 1311887 (Reprint of the 1918 Cambridge University Press edition.)