| Darius II 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 | |

|---|---|

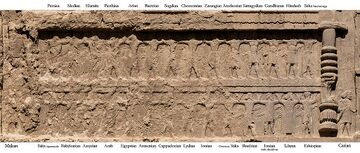

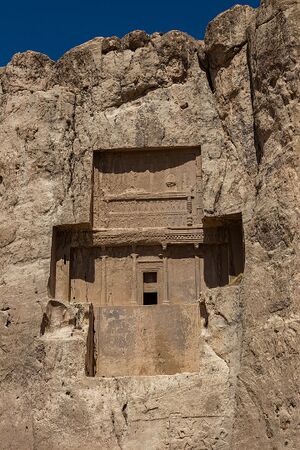

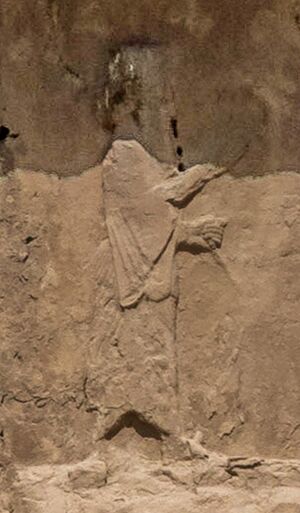

Darius II as depicted on his tomb in Naqsh-e Rostam | |

| King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire | |

| Reign | 423–404 BC |

| Predecessor | Sogdianus |

| Successor | Artaxerxes II |

| Died | 404 BC |

| Spouse | Parysatis |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Achaemenid |

| Father | Artaxerxes I |

| Mother | Cosmartidene of Babylon |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Darius II (Old Persian: 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.; Greek: Δαρεῖος Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.), also known by his given name Ochus (Greek: Ὦχος Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 423 BC to 405[1] or 404 BC.[2]

Artaxerxes I, who died in 424 BC, was followed by his son Xerxes II. After a month and half Xerxes II was murdered by his brother Sogdianus. His illegitimate brother, Ochus, satrap of Hyrcania, rebelled against Sogdianus, and after a short fight killed him, and suppressed by treachery the attempt of his own brother Arsites to imitate his example. Ochus adopted the name Darius (Greek sources often call him Darius Nothos, "Bastard"). Neither the names Xerxes II nor Sogdianus occur in the dates of the numerous Babylonian tablets from Nippur; here effectively the reign of Darius II follows immediately after that of Artaxerxes I.[2]

Historians know little about Darius II's reign. A rebellion by the Medes in 409 BC is mentioned by Xenophon. It does seem that Darius II was quite dependent on his wife Parysatis. In excerpts from Ctesias some harem intrigues are recorded, in which he played a disreputable part.[2] The Elephantine papyri mention Darius II as a contemporary of the high priest Johanan of Ezra 10:6.[3][4]

Conflict with Athens

As long as the power of Athens remained intact he did not meddle in Greek affairs. When in 413 BC, Athens supported the rebel Amorges in Caria, Darius II would not have responded had not the Athenian power been broken in the same year at Syracuse. As a result of that event, Darius II gave orders to his satraps in Asia Minor, Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus, to send in the overdue tribute of the Greek towns and to begin a war with Athens. To support the war with Athens, the Persian satraps entered into an alliance with Sparta. In 408 BC he sent his son Cyrus to Asia Minor, to carry on the war with greater energy.

Darius II may have expelled various Greek dynasts who had been ruling cities in Ionia: Pausanias wrote that the sons of Themistocles, which include Archeptolis, Governor of Magnesia, "appear to have returned to Athens", and that they dedicated a painting of Themistocles in the Parthenon and erected a bronze statue to Artemis Leucophryene, the goddess of Magnesia, on the Acropolis.[5][6][7] They may have returned from Asia Minor in old age, after 412 BC, when the Achaemenids took again firm control of the Greek cities of Asia, and they may have been expelled by the Achaemenid satrap Tissaphernes sometime between 412 and 399 BC.[5] In effect, from 414 BC, Darius II had started to resent increasing Athenian power in the Aegean and had Tissaphernes enter into an alliance with Sparta against Athens, which in 412 BC led to the Persian conquest of the greater part of Ionia.[8]

Darius is said to have received the visit of Greek athlete and Olympic champion Polydamas of Skotoussa, who made a demonstration of his strength by killing three Immortals in front of the Persian ruler.[9][10] A sculpture representing the scene is visible in the Museum of the History of the Olympic Games of antiquity.[11]

Darius II died in 404 BC, in the nineteenth year of his reign, and was followed as Persian king by Artaxerxes II.[2]

Issue

Prior to his accession, Darius II was married to the daughter of Gobryas. With the daughter of Gobryas, Darius II had four sons, one of whom fathered Artabazanes, who served as King of Media Atropatene in the second half of the 3rd century BC.[12][13][14]

- By Parysatis

- Artaxerxes II

- Cyrus the Younger

- Oxathres or Oxendares or Oxendras

- Artoxexes

- Ostanes

- Amestris wife of Teritouchmes & then Artaxerxes II

- & seven other unnamed children

See also

References

- ↑ Brill's New Pauly, "Darius".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Pritchard, James B. ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, Princeton University Press, third edition with supplement 1969, p. 492

- ↑ Bezalel Porten (Author), J. J. Farber (Author), C. J. F. Martin (Author), G. Vittmann (Author), The Elephantine Papyri in English (Documenta Et Monumenta Orientis Antiqui, book 22), Koninklijke Brill NV, The Netherlands, 1996, p 125-153.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Paus. 1.1.2, 26.4

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ ARTABAZANES, Encyclopedia Iranica

- ↑ García Sánchez, M (2005): "La figura del sucer del Gran Rey en la Persia Aqueménida", in V. Troncoso (ed.), Anejos Gerión 9, La figura del sucesor en las monarquías de época helenística.

- ↑ Hallock, R (1985): "The evidence of the Persepolis Tablets", in Gershevitch (ed.) The Cambridge History of Iran v. 2, p. 591.

Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 158: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).