| Artaxerxes I 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 | |

|---|---|

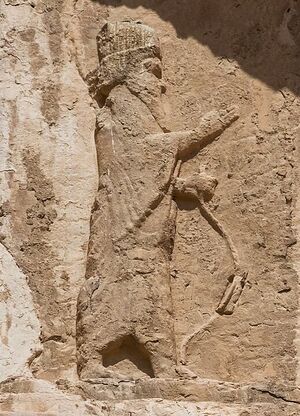

Relief of Artaxerxes I, from his tomb in Naqsh-e Rustam | |

| King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire | |

| Reign | 465–424 BC |

| Predecessor | Xerxes I |

| Successor | Xerxes II |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | 424 BC, Susa |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Damaspia Alogyne of Babylon Cosmartidene of Babylon Andia of Babylon |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Achaemenid |

| Father | Xerxes I |

| Mother | Amestris |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

| ||||||||

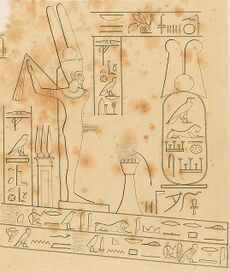

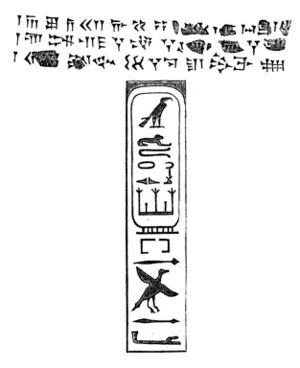

| Artaxerxes[1] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Late Period (664–332 BC) | ||||||||

Artaxerxes I (/ˌɑːrtəˈzɜːrksiːz/, Old Persian: 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.;[2][3] Greek: Ἀρταξέρξης)[4] was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC.[5][6] He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the "Artasyrus" mentioned by Herodotus as being a satrap of the royal satrapy of Bactria.

In Greek sources he is also surnamed "long-handed" (Ancient Greek: μακρόχειρ Makrókheir; Latin: Longimanus), allegedly because his right hand was longer than his left.[7]

Succession to the throne

Artaxerxes was probably born in the reign of his grandfather Darius I, to the emperor's son and heir, Xerxes I. In 465 BC, Xerxes I was murdered by Hazarapat ("commander of thousand") Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard and the most powerful official in the Persian court, with the help of a eunuch, Aspamitres.[8] Greek historians give contradicting accounts of events. According to Ctesias (in Persica 20), Artabanus then accused Crown Prince Darius, Xerxes's eldest son, of the murder, and persuaded Artaxerxes to avenge the patricide by killing Darius. But according to Aristotle (in Politics 5.1311b), Artabanus killed Darius first and then killed Xerxes. After Artaxerxes discovered the murder, he killed Artabanus and his sons.[9][10]

Egyptian revolt

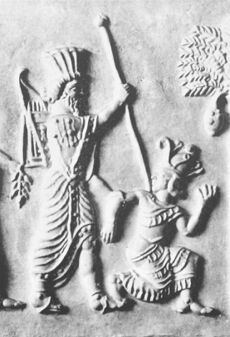

Artaxerxes had to face a revolt in Egypt in 460–454 BC led by Inaros II, who was the son of a Libyan prince named Psamtik, presumably descended from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. In 460 BC, Inaros II revolted against the Persians with the help of his Athenian allies, and defeated the Persian army commanded by satrap Akheimenes. The Persians retreated to Memphis, and the Athenians were finally defeated in 454 BC, by the Persian army led by Megabyzus, after a two-year siege. Inaros was captured and carried away to Susa.

Relations with Greece

After the Achaemenid Empire had been defeated at the Battle of the Eurymedon (c. 469 BC), military action between Greece and Persia was at a standstill. When Artaxerxes I took power, he introduced a new Persian strategy of weakening the Athenians by funding their enemies in Greece. This indirectly caused the Athenians to move the treasury of the Delian League from the island of Delos to the Athenian acropolis. This funding practice inevitably prompted renewed fighting in 450 BC, where the Greeks attacked at the Battle of Cyprus. After Cimon's failure to attain much in this expedition, hostilities ceased. Later sources argue that the purported Peace of Callias was agreed among Athens, Argos and Persia in 449 BC; however, the existence of a formal treaty between the Greek States and Persia is disputed.

Artaxerxes I offered asylum to Themistocles, who was probably his father Xerxes's greatest enemy for his victory at the Battle of Salamis, after Themistocles was ostracized from Athens. Also, Artaxerxes I gave him Magnesia, Myus, and Lampsacus to maintain him in bread, meat, and wine. In addition, Artaxerxes I gave him Skepsis to provide him with clothes, and he also gave him Percote with bedding for his house.[12] Themistocles would go on to learn and adopt Persian customs, Persian language, and traditions.[13][14]

Portrayal in the Book of Ezra and Nehemiah

A King Artaxerxes (Hebrew: אַרְתַּחְשַׁשְׂתְּא, אַרְתַּחְשַׁ֣סְתְּא, pronounced [artaχʃast(ǝ)], or אַרְתַּחְשַׁ֗שְׂתָּא pronounced [artaχʃasta]) is described in the Bible (Ezra 7) as having commissioned Ezra, a kohen and scribe, by means of a letter of decree to take charge of the ecclesiastical and civil affairs of the Jewish nation.

Ezra thereby left Babylon in the first month of the seventh year[15] of Artaxerxes' reign, at the head of a company of Jews that included priests and Levites. They arrived in Jerusalem on the first day of the fifth month of the seventh year according to the Hebrew calendar. The text does not specify whether the king in the passage refers to Artaxerxes I (465–424 BC) or to Artaxerxes II (404–359 BC).[16][17] Most scholars hold that Ezra lived during the rule of Artaxerxes I, though some have difficulties with this assumption:[18] Nehemiah and Ezra "seem to have no knowledge of each other; their missions do not overlap", however, in Nehemiah 12, both are leading processions on the wall as part of the wall dedication ceremony. So, they clearly were contemporaries working together in Jerusalem at the time the wall and the city of Jerusalem was rebuilt in contrast to the previously stated viewpoint.[19] These difficulties have led many scholars to assume that Ezra arrived in the seventh year of the rule of Artaxerxes II, i.e. some 50 years after Nehemiah. This assumption would imply that the biblical account is not chronological. The last group of scholars regard "the seventh year" as a scribal error and hold that the two men were contemporaries.[18][20] However, Ezra appears for the first time in Nehemiah 8, having probably been at the court for twelve years.[21]

The rebuilding of the Jewish community in Jerusalem had begun under Cyrus the Great, who had permitted Jews held captive in Babylon to return to Jerusalem and rebuild Solomon's Temple. Consequently, a number of Jews returned to Jerusalem in 538 BC, and the foundation of this "Second Temple" was laid in 536 BC, in the second year of their return (Ezra 3:8). After a period of strife, the temple was finally completed in the sixth year of Darius, 516 BC (Ezra 6:15).

In Artaxerxes' twentieth year, Nehemiah, the king's cup-bearer, apparently was also a friend of the king as in that year Artaxerxes inquired after Nehemiah's sadness. Nehemiah related to him the plight of the Jewish people and that the city of Jerusalem was undefended. The king sent Nehemiah to Jerusalem with letters of safe passage to the governors in Trans-Euphrates, and to Asaph, keeper of the royal forests, to make beams for the citadel by the Temple and to rebuild the city walls.[22]

Interpretations of actions

Roger Williams, a 17th-century Christian minister and founder of Rhode Island, interpreted several passages in the Old and New Testament to support limiting government interference in religious matters. Williams published The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience, arguing for a separation of church and state based on biblical reasoning. Williams believed that Israel was a unique covenant kingdom and not an appropriate model for New Testament Christians who believed that the Old Testament covenant had been fulfilled. Therefore, the more informative Old Testament examples of civil government were "good" non-covenant kings such as Artaxerxes, who tolerated the Jews and did not insist that they follow his state religion.[23]

Medical analysis

According to a paper published in 2011,[24] the discrepancy in Artaxerxes’ limb lengths may have arisen as a result of the inherited disease neurofibromatosis.

Children

By queen Damaspia

By Cosmartidene of Babylon

- Bogapaeus

- Parysatis, wife of Darius II Ochus

By another(?) unknown wife

- An unnamed daughter, wife of Hieramenes, mother of Autoboesaces and Mitraeus[27]

By various wives

- Eleven other children

See also

References

- ↑ Henri Gauthier, Le Livre des rois d'Égypte, IV, Cairo 1916 (=MIFAO 20), p. 152.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Artaxerxes at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ The Greek form of the name is influenced by Xerxes, Artaxerxes at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Plutarch, Artaxerxes, l. 1. c. 1. 11:129 - cited by Ussher, Annals, para. 1179

- ↑ Pirnia, Iran-e-Bastan book 1, p 873

- ↑ Dandamayev

- ↑ Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire, pp 289–290

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Thucydides I, 137

- ↑ Plutarch, Themistocles, 29

- ↑ The Book of Daniel. Montex Publish Company, By Jim McGuiggan 1978, p. 147.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Ezra". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ John Boederman, The Cambridge Ancient History, 2002, p. 272

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Nehemiah 2:1–9

- ↑ James P. Byrd, The challenges of Roger Williams: Religious Liberty, Violent Persecution, and the Bible (Mercer University Press, 2002)[1] (accessed on Google Books on July 20, 2009)

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ Lua error in Module:Citation/CS1/Configuration at line 2123: attempt to index field '?' (a nil value).

- ↑ The vase is now in the Reza Abbasi Museum in Teheran (inv. 53). image inscription

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenica, Book II, Chapter 1

External links

Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 158: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).