Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

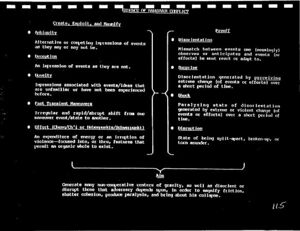

You want to generate alternative or competing events in a guy's mind, as many as possible. He can't figure out what the hell is going on. That's ambiguity, because they may or may not be. You're trying to generate is mental confusion and disorder so he can't cope with unfolding circumstances. That's what ambiguity is. Deception, an impression of events as they are not. Really a neat picture, only it’s a wrong picture of what's going on. Let's juxtapose them. If you look at ambiguity, it's easier to generate than deception. In other words, you can generate confusion and disorder more rapidly than you generate an order, even though it's a false order. It takes longer to generate a deception over ambiguity.

Ambiguity is also less risky than a deception. Less risky. That doesn't mean you shouldn't have a deception. In Normandy— the Normandy case is a good example, because if you can realize it, you get enormous leverage out of deception. But remember, it's riskier and it takes longer. We really didn't understand that during World War II. In fact, I don't think many of us understand it to this day.

Let me give you an example. Operation TORCH, the invasion of North Africa. We set up a big deception campaign. We virtually got on scot-free, but hit some problems later on after we drive in on it. We got in there, got a free ride in, in a sense. But then after they looked at it, they ran a critique on it, and the deception masters had to admit that the deception campaign didn't succeed. Instead, they said it was a success of security. Well, when you read into it— Christ, the Germans didn't know what we were going to do. They had all— we created all kinds of impressions, so it was a success of ambiguity. That's what it was. And Normandy is the opposite case. We had a lot of time to set that thing up. Lots of time.

So, we created in the German mindset the idea that we were going to come in the Pas-de-Calais area, and even after we landed at Normandy, we kept up the deception, so they think it was only a secondary effort. And they still had that for over thirty days in their mind, while our whole effort was in Normandy. It was Normandy. Which is an extraordinary deception. In other words, they didn't stop it once we got there, they kept going all the time, thinking we were still going to land.

And to show you we didn't understand it, once again in Italy, they said how come we couldn't get a deception to work there? We didn't have time. Christ, we were exploiting an existing situation after Sicily, going to Italy, and that's the advantage of an ambiguity. You don't need a lot of time. Deception takes a lot of time to set up.

And that’s what blitzkrieg does. Once you may have an initial deception, but once you start riding, you’re riding on what? You're riding on ambiguity, not on deception. You can't stop the operations to set up a new deception. You ride on ambiguity when you’re exploiting an existing situation.

And another thing, novelty. That's one thing technology gives you, are new ideas. In other words, create situations the guy's never been aware of before. He didn't know what to do. He's never experienced it before. Whether it's technology, whether you've got a new wrinkle in how to set up an operation, or whatever. You face a novel situation, can't cope.

And then fast transient maneuvers. Not only rapid, but also irregular and rapid, so he can't get an image of what's going on. And your effort, directly against those features that permit him to retain his organic wholeness.

So if you pull all those together, what's your payoff? You’re deliberately trying to generate a disorientation in his mind, mismatch between what he anticipates and that which he must react to, to survive. A mismatch. Now if you think about that, you can redefine surprise. Surprise is nothing more than a disorientation. It doesn't say that, but that's what it is. You can get it either from ambiguity, deception, or any combination. It may take a long period of time, but generally it's a disorientation generated by perceiving an extreme change. It doesn't mean it happened over a short period of time, but you perceived it. All of a sudden you say, my God, what happened? It may have been working itself out for a long, or it may be just speed.

So, surprise is nothing more than a form of disorientation. Likewise, shock, except in this case shock is so awesome, it’s so paralyzing, Christ, you don't know what to do. You go into a state of shock. I look at shock as nothing more than a hard surprise. You can look at surprise as a soft shock. They’re both forms of disorientation.

[15:00] And disruption, the state of being split apart, broken up, or torn asunder. So all these things, you're trying to realize this kind of an aim. But now we've done something interesting here. Since we’ve defined surprise and shock as a form of disorientation, why not just remove them from the board and look at disorientation and disruption? Before we do that, let's look at it a little bit more carefully. We may want to do it, but let’s look at it a little bit more carefully.