Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

So if you want to boil that down, [20:00] here’s the essence of the whole thing. Here’s the intent behind it and the implication associated with it. In order to counter that, you’ve got to set up sort of a counter-game, and that’s what the CAP[1] teams were trying to do in Vietnam. And of course, that’s not fighting a war with ways— you know, you’re not allowed to do “search and destroy” operations there so we got out of that, said, hell, we can’t do that “search and destroy” stuff.

How many people here saw the movie Platoon, by any chance? It can’t just be me. What was the central message that came out of that? There is a central message. What was a big event in there? Remember, it was the attack upon the village. Remember that?

And a lot of Marines and other people get mad. They say well, you shouldn’t be showing the American people that. That stuff happened. You can’t call these guys murderers. That’s true. But it happened. They’re not calling them murderers. But what’s the whole point of that?

I’m trying to hint and tell you something. We shouldn’t be attacking those goddamn villages. We should’ve been in the villages to try to get the other guy to attack it. Then he’s the enemy. And that’s what the CAP teams tried to do. We worked the problem the wrong way. Exactly the wrong way.

And the initial CAP teams that were sent over there, and the initial Special Forces, were trying to do that. Oh, hell, that takes too long. See, they understood it. You subdue the enemy without any fighting. Make the other guy do it. Then he’s the enemy. Then you got the leverage on your side. And Mike can tell you about them guys were over there.

Tell them about that situation, that one time when you were there, what happened, Mike, when they pulled you off that. It’s a very important point right now.

Wyly: —1965 and—

Boyd: It’s a real important point.

Wyly: We were working on the people and getting a good number of defectors to come in, and then using the defectors to go out and get other defectors. And as time went on, we put a message out to the people that— and this came from division and headquarters.

We had authority to tell the people that the Marines were going to stay. Because it was a big question in the people’s mind. They used to ask me a lot of times when I’d operate in the villages. I was just a first lieutenant. Are the Marines going to stay here or not? Are y’all going to leave? And I went in to the Chief of Staff and tried to get in to the General, and get an answer. And finally, I was very naive. I was a first lieutenant. They kind of gaffed me off, oh, oh, we’re going to stay. We’re going to stay here.

So we put that out in leaflets and by word of mouth, everyone we could, Marines are here to stay. Then we took off and left and went out into the hills to search and destroy—

Boyd: You were ordered to. You didn’t want to. You had no choice.

Wyly: That’s right. No choice at all. Well, and then we came back again, the families of the people that had been working with me had been assassinated. And we never got any more defectors again. You know, we got zero cooperation.

Boyd: Now you have to attack the villages.

Wyly: And my Colonel— when I went back to the Colonel and told him what happened, he said Lieutenant, you killed them. You killed them. You murdered them. You're the murderer. So I went back and sorted that out for a few years. But that’s in a nutshell, a very true story actually.

We didn’t understand the whole [unintelligible].

Boyd: See Sun Tzu says, subdue the enemy without any fighting. You don’t want to go out into the weeds out there. You want to own all the people. And next thing, the other guy has no resource to work with.

Audience: But in order to do that, you’re going to have to be willing to enter into protracted warfare, not only the military men but also the civilian population, so you have to—

[Cross talk]

Boyd: That’s right. You have to be willing to play the game so you can leverage the game.

That’s right. Magsaysay understood that. Do we understand? Do we? I don’t think so to this day.

I’d like to say yes, but if I say yes, I have a feeling I’m telling one hell of a lie.

Audience: Oh, no, I think the military understands, the population doesn’t. I don’t think the military’s willing to do this, protracted war.

Boyd: I think a lot of military people are not— I think that we’re coming to terms with it, at least some people. But I think as an organic body, I don't think we still— well, look at down in Central America. We still— you know, that’s a more recent one. We’ve still gooned that damn thing. Not that we shouldn’t have been there, but the way we go about it.

Wyly: If the alternative is not to do protracted war and lose, okay. Do that. Do it another way and lose. I think we’re less willing to lose than do protracted war, if we think it through. Although I’m not saying, I’m not buying onto that protracted war. I think there’s some quicker ways to do it.

[Cross talk]

Boyd: I think you can do it rapidly, I think you don’t have to have it protracted per se. But it’s not going to go at this so-called blitzkrieg pace you want to go at.

Wyly: Yeah, but if the alternative is doing it protracted and having a chance of winning, or doing it fast and losing, that may sound ridiculous but—

Boyd: See Magsaysay[2] did, when he—after he got on board, which I’ll get into later on, he wrapped it up in two years.

Audience: Who’s that, sir?

Boyd: Magsaysay. Ramon Magsaysay, when he came on board. They were going down the tubes. In two years, he turned the whole thing around.

Wyly: And we had that whole example before us, before we went to Vietnam.

Boyd: It was all there.

Wyly: I studied Magsaysay inside and out as a first lieutenant when I went over there in 1965.

[25:00] And those examples were there. Combat history examples, problem books and— Boyd: He did it in two years. You can’t say that’s real long. It takes a little time. But he turned the whole goddamn thing around. Got in there, got it cleaned out. The guerrillas did it in two years. They were going down the tubes. From defeat to victory in two years.

Wyly: We use that model for our [unintelligible] for setting it up. That was one of the models that we used.

Boyd: Defeat to victory.

Wyly: And the information was out there.

Boyd: It was out there, but you know, that’s not those nice European plains. You’ve got tanks thundering through, personnel carriers, close air support, and all that stuff. That’s not our way. Audience: Where was that, Colonel?

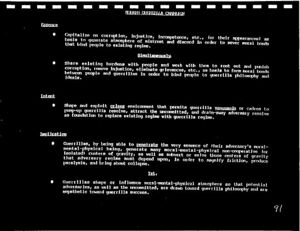

Boyd: Magsaysay, Philippines. So here’s what you’re trying to do. You shape and exploit crises and then use this, like we said before, so the implication’s very clear. You’re trying to penetrate the very essence of the adversary’s moral-mental-physical scheme. Generate the many non-cooperative centers of gravity. That’s the message. Go ahead.

Audience: It’s obvious, but it applies to the understanding of the language and culture and religion.

Boyd: Precisely. Precisely. How many people read— there’s a book out on that where he brings it out very vividly, Silence Was a Weapon by Herrington.[3] He pointed that out. It’s a very nice book, if you haven't read it. I think it’s still out in soft cover. It was about four or five years ago when it came out. It’s a damn good book.

And he learned the Vietnamese language, but then he pretended he didn’t know it. So he went over there and pretended he didn’t know it. And he was sucking up all kinds of information. So he took the object.

He learned the things, though. Very few people knew he knew it, and then he would go in these places made out as a dumb American, and he was listening to them. He was sucking up all kinds of information. So he did a double whammy on them. He said, prove that you’re invaluable. It’s a very interesting book. He didn’t always do that. There’s some instances, if you recall, he’s playing that kind of a game.

So it’s important you understand the culture. We’re going to get into that in just a minute. You’re onto something. We’re going to talk here in just a minute.

[Cross talk]

Audience: That’s going to require a long-term investment, I mean— not long-term but handsome investment into the individual—

[Cross talk]

Boyd: Well, goddamn it, don’t you want to make that investment? Don’t you want to win? Screw it. Oh, no, we’re going to do it over the weekend. We’re going to win this goddamn war over the weekend.

Audience: I hear you, sir.

Boyd: That’s not the American way, is it? Yeah, we’ve got the weekend to do this. Okay.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 35 Combined Action Platoons.

- ↑ 36 Ramon Magsaysay was serving in the Philippine Army when World War II began. After invading Japanese forces successfully captured the islands and caused the American surrender at Bataan, Magsaysay evaded capture and organized a guerrilla resistance until American forces returned in 1945. In 1950, with the Philippines facing a new insurgency from communist Hukbalahap guerrillas, Magsaysay was appointed Secretary of National Defense and led a successful counterinsurgency campaign against them.

- ↑ 37 Stuart A. Herrington, ''Silence was a Weapon: The Vietnam War in the Villages'' (New York, NY: Presidio Press, 1982).