Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

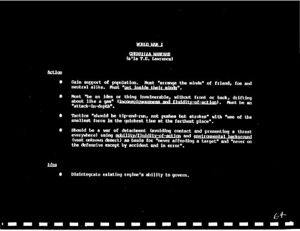

Okay. Let’s go to guerrilla now. It’s only one chart. Lawrence. Now remember, Lawrence was a scholar. I think he was from Oxford, Cambridge, I can’t remember. He read a lot about this stuff. And he came up with the idea you’ve got to gain support of the population, very modern context. Arrange the minds of friend, foe, and neutral alike. Get inside their minds. He recognized it’s mental. And then note this, he said, “be an idea or thing invulnerable, without front or back, drifting about like a gas.” In other words, he’s not defending the terrain. He’s using the terrain to present some kind of an amorphous image to his adversary, so they can’t come to grips with him.

In other words, he not only has fluidity, but he’s got inconspicuousness. In other words, it’s even more delicate than water. He’s going to behave like a gas than like water. You’re bringing the idea of fluidity of action, plus the inconspicuousness, or indistinctness. And note this, another quote, “should be tip and run, not pushes but strokes, quickest time at the furthest place.” What’s he doing here by doing all this stuff? He’s trying to present a threat everywhere, but yet seem to be nowhere.

In other words, it’s like the Mongols. Remember, we read about the Mongols. Remember we said that’s the kind of thing they were doing. And so he said, it should be a war of detachment, avoiding contact, presenting a threat everywhere, using this mobility, fluidity of action, and environmental background.

And that’s what he did. He was working the Hejaz railroad. He was trying— what he did— actually he was the cheng where Allenby[1] was a chi for going into Palestine. What he was trying to do is, by doing all this action around the railroad, is to force the Turks to put in more and more troops and supplies there, and then drain away from their effort for defending the rest of Palestine, which made it easier, then, for Allenby to make his stroke into Palestine. So in this case, the guerrillas were the cheng and the regular force was the chi, if you want to use that Sun Tzu relationship there in that conflict.

But the thing you see here, as well as in the infiltration tactics, they’re using the terrain as a medium in order to get, what, leverage over their adversary. Not to defend the terrain, per se, but as a medium to gain leverage on him. That’s exactly right.

Now I’m not going to use this later on, but remember what Mao said. Remember he said there’s three phases to a guerrilla campaign. So I’ll preempt myself. I’ll tie it right into this, since I won’t use this particular statement later on when I get more into guerrilla stuff. He said remember, you’ve got the strategic defensive, strategic equilibrium, strategic offence. But in all three, it’s tactical offense, tactical offense, tactical offense.

[30:00]Remember, strategic defense means you’re backing up, and he’s still talking about tactical offense. What’s he really saying? What he’s saying, it doesn’t make any difference whether you’re going forward or backward. The key thing, do I or do I not have the initiative. And as long as I’m getting the other guy to do the things that I want him to do, rather than what he wants to do, then I have the initiative, makes no difference which direction you’re going in.

So therefore, another way to look at initiative is what? I get inside my adversary’s OODA loops, I got the initiative. If he gets inside my OODA loops, he’s got the initiative. And the reason why OODA loops are important, because they’re all human terms. People have to observe. They have to orient. They have to decide. And they have to act. And if you’re getting inside that, you’re getting inside that guy’s rhythm, his tempo, his natural way of doing business. He can’t play.

And that’s why it’s important. I don’t care whether you go slow or fast. People say no, we’re going to drive fast— no, no. As long as you— I don’t care if you’re slow, if you can slow him down even slower. It’s all relative. So you can tie initiative directly to that. Then of course the idea is very simple. I actually prettied it up a little bit. These are my statements, but that’s what he was getting at.

But basically his statements where he was— quoting him, he said the idea is to extrude the Turks from Arabia. That’s what he was trying to do. That was an exact quote there from Lawrence, extrude the Turks from Arabia. So what he’s doing, he’s disintegrating a regime, even the ability to govern. And so here’s the impression then.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 23 Field Marshal Edmund Allenby commanded the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Palestine from 1917-1918 during World War I. His campaigns on the Sinai peninsula and in Ottoman-held Palestine drove the Ottoman armies from much of the Middle East and eventually forced their capitulation. T.E. Lawrence fell under his command.