Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

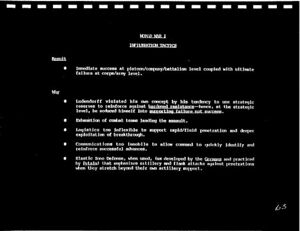

Okay. Now, let’s move on. So in a sense, it still failed. Remember, they had success in the lower level and failed at the upper levels. So why did that happen? Well, here’s some good reasons [unintelligible]. One: you can only start out successful. Once it started, when he gets resistance, he starts fighting against that resistance. In other words, you reverted back to type, strength against strength. In order to start supporting failure. Also, exhaustion of the combat

team leading the assault. He didn’t replace the team, same team. Later on, like in World War II, the Germans had a reserve, and they would insert the reserve and have a rotation policy for the leading edge units and the other units, so they could keep the operation going.

And logistics, they had to set up the logistics in order to handle those kind of things. And here’s a very key one, communications that they set up. Remember, if you’re going to use this kind of a technique, once it starts, the rear level commander now really needs that information flow coming from the front, who’s succeeding and who isn’t. Because depending upon who’s succeeding and who isn’t, that’s how he’s going to allocate the follow-on efforts, so he can go through those gaps. If he doesn’t know who’s succeeding and who isn’t succeeding, he doesn’t know how to allocate people. He’s got to make some kind of an allocation, but it’s not going to be a very bright one.

And see, that’s one thing you have when you go strength against weakness, you have to know where the weakness is, who’s succeeding and who isn’t. And once they understand that, then they can reallocate or shift the schwerpunkt as we talk about nowadays, or the focus of effort. Go ahead.

Audience: When you talk about the immobility of the communications—

Boyd: World War I. Yeah, they had telephone lines. They didn’t have the radios we have now. I’m talking about, Christ, they had to string telephone lines. Of course, artillery would be in and cut the telephone lines, and it’s hard to string it. Remember, they didn’t have much radio then. They had a lot of telephones.

Audience: I was going to say, the immobility of not being able to move the phones lines verses—

Boyd: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it’s sort of a— it’s the best they had at the time. Relative to what they needed, it caused some problems. Christ, they were trying to run out the wire all the way up all the time.

Audience: And yet, it was a vast improvement over communications pre-Civil War.

Boyd: Exactly. Exactly. And of course, nowadays, we have— our communications are fantastic. Of course, in some ways they cause a lot of problems. We depend too much on them. And as I’ll point out when we get to World War II, Guderian understood that. When you depend upon it too much, it can cause you some problems. He understood that, because we had a lot of radios during World War II.

Okay. So in that sense, when you think of it this way, in a sense it sort of softened some of the harshness. And of course, the idea of the elastic in-zone defense. Instead of this rigid defense, you have a flexible or a fluid defense. In other words, you pull back from the onslaught. Let your people come back, and then you draw the other guys out beyond their own artillery. You dump yours in, then start choking them off from the flanks and the rear.

But you have to have confidence to do that. People normally say, oh, we’re just going to stand fast and we’ll blow people away. Sometimes you want to pull back. Anybody ever read Manstein’s Lost Victories?[1] Remember how he said take that long step backward, get them in, and cut their balls off. In other words, he’s using the terrain as a medium for maneuver.

Audience: [25:00] There are no lines.

Boyd: That’s right. There are no lines. That’s right. The FEBAs,[2] the lines, that’s all— the only time you have a FEBA is before operations start. After that, nobody knows where it is. So you’re trying to put these FEBAs on the map after they started. It’s a hopeless effort. It didn’t represent anything that was going on.

If you have a chance, you ought to read his Lost Victories. It’s very good. Boy, he takes that long step backward, gets the guy strung out, and then cuts his balls off. He gets a whole bag full of prisoners. Christ, their morale’s shot to hell and everything else. He’s not the only one. He just describes it very well. Other ones did it too. They said we’re not going to give up an inch of ground. You put your guys in your trench and start pounding that.

So when you think of it this way, what are you thinking about? The terrain rather than being— trying to hold the terrain, per se, using the terrain as a medium of maneuver so you can take out the force. Remember what I said? Terrain doesn’t fight wars. Machines don’t fight wars. People do it. And they use their minds. In that context, using the terrain is a medium through which you’re going to maneuver in order to gain leverage on his force.

I don’t care whether you’re going forwards, backwards, or side wards or any direction. As long as you have the— you can have initiative going backwards too, you know. See, we’re taught if we’re going backwards, we’ve lost initiative. That’s not true. As long as you got him playing your game rather than playing his game, you have initiative. And I don’t care which direction you’re going in.

Audience: Does that necessarily mean you have to take— look at terrain as fluidity vice an obstacle—

Boyd: Now— Normally you want to— terrain’s important.

Audience: But what I’m saying is, rather than looking at terrain as an obstacle, you’re looking at it, as you said, as—

Boyd: You can look at it— yeah, sometimes you also want to use the obstacles in order— by having obstacles there and reinforce those obstacles, you can get them to flow in a certain direction, too. But don’t say because that’s an obstacle, we make the whole terrain an obstacle and we’re going to stand fast. That’s what I’m trying to tell you.

See, because sometimes, you can use a certain kind of terrain. You can say, well, we can set stuff up so he has to go in a certain direction. We can cut him later on too. Nothing wrong in it. That’s good thinking. But not to use the whole terrain as reinforced— using obstacles so they can’t go up against it. That’s my argument.

But you’ve got to get that in line. Remember, use the terrain as a medium through which you’re going to take out his force. Not to defend it per se, but as a medium so you can take out his force.

Because once you take out his force, you own the terrain whether you’re going forwards, backwards, side wards, or any direction. Then you own it.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 21 Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, ''Lost Victories: The War Memoirs of Hitler’s Most Brilliant General,'' trans. Anthony G. Powell (St. Paul, MN: Zenith Press, 2004). One of the German Army’s most senior commanders during World War II, Manstein planned both the successful invasion of France in 1940 and several operations against the Red Army on the eastern front. He was eventually relieved of command by Hitler in 1944 for disobeyed Hitler’s orders to hold all territory to the last man. While Manstein’s position in the midst of multiple major operations during World War II make his memoir worth reading, his book has also been criticized as self-aggrandizing and white-washing those parts of the Holocaust which occurred in territory over which he had command.

- ↑ 22 Forward Edge of the Battle Area.