Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

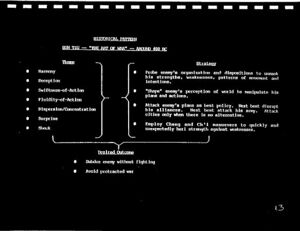

Okay, with that in mind, now let’s go through the history. I’m sure many of you have read, Sun, how many people read Sun Tzu? I’m sure a lot of you have read Sun Tzu. And you’ll get some arguments about when he wrote the thing, or whether he or somebody else wrote it before him, I’m not going to go through all that. You know, 400 BC, 500 BC, if I took the average around 400.

But his theme, harmony. How many people saw that? In his very first chapter, what is he talking about? The citizens have to be in accord with the, the subjects have to be in accord with the rulers of the state, you have to be in harmony with the rulers. In other words, if you can’t get the people working with the rulers, you can’t go to war. As a matter of fact, that’s what the Vietnamese did to us. They got us so we weren’t in accord with one another, and we had to depart from that war in Vietnam.

Deception, and more than once, it’s laced through, all war, his famous statement, is based on deception. We’re going to look at that detail later on, how that plays with other stuff. And the idea of speed, rapidity, or swiftness of action. In fact he says the essence of war is speed, rapidity, swiftness of action. Brings that up. And then in a very indirect way, brings this thing, what I call fluidity of action. Remember he said an army should behave like water going downhill, seeking the crevices, avoids the gaps, and strength against weakness. That’s the fluidity argument.

Now if you recall, when you first read the thing, if you never read it before, first thing you do, you say, what’s this guy saying? Looks like he’s saying some important stuff, but he’s using metaphors, analogies, and aphorisms, and you got to read, pretty soon, it’s a polite way of discussing conflict. In other words, the Chinese are bending themselves at the knees [unintelligible].

Fluidity of action. Why? Three things you can get advantage of from that, what do you get? One, gives you the opportunity to do what? Strength against weakness. That’s one idea that comes out of it. The idea of moving along paths of least resistance. And the third idea from fluidity is what?

The idea of being fluid and you’re what? You’re adapting. Adaptability. Strength against weakness, paths of least resistance, adaptability. All three of those in [unintelligible]. So we take all these together, harmony, deception, swiftness of action, fluidity, then with those four together, you can play the so-called dispersion/concentration game. Not just concentration, but also dispersion.

So what do we have in our principles of war? Concentration, no dispersion. But Sun Tzu had both. How many people are infantrymen here? How would you like to take a bunch of guys, nice and concentrated, and attack against a machine gun? It’d clean your ass out. It’s concentrated. You say, wait a minute. I want to spread them out a little bit. Yeah.

So what about that? You know, we say, well, we got a caveat; when you keep caveating the principle of concentration, pretty soon there’s no meaning. That’s just one example.

Okay then, by playing all these together, you can generate what I call surprise and shock. Too often we treat surprise as input and shock as input. ''[10:00]''I don’t surprise you, you don’t surprise me. I do certain things, you can’t keep up. You become surprised. Surprise is an output, not an input. It’s a reaction, because you couldn’t keep up, you didn’t pay attention, whatever the case may be. Or you’re overwhelmed by what has happened.

The only difference between surprise and shock, as I’ll bring out later on, shock is just a hard form of surprise, it’s also an output. You get paralyzed, knocked so hard you can’t cope. But they’re both output. And they’re both, I might add, in conflict, very desirable features to have the other guy have, not you.

You don’t surprise me. I’m really surprised when you do certain things and I don’t react, I’m surprised. [unintelligible] Output. You look at the principles of war, they got them all screwed up. They got input mixed in with output, that’s another bad thing about them. They can’t even get the goddamn thing sorted out right.

So you want to ask yourself, what kind of things do I do besides these, if I want to look at a deeper sense later on, that permit me to get that thing we call surprise out of our adversary? In other words, where he is not able to react, or keep up with events, so he can do the right kind of thing?

What do you want to call it? Surprise, if it’s a softer form, or a harder form, we call it shock. You don’t give shock, it’s a state of shock you put the guy in. So that’s his theme.

And his strategy, you all heard this, probe enemy’s organization, disposition, strength against weakness, patterns of movement, et cetera. All those kinds of things. Not only that, he had in the last chapter, remember, he talked about all the uses of spies. In fact, he used the term “double agents” in his day. We thought we invented it, it goes all the way back to 400, 500 BC. He’s talking about double agents. In fact, that was his most valuable agent, if you recall.

So get inside, know your adversary, that’s the thing. Know your enemy. Any way you can. As a result of that, then you can shape his perception of the world, so you can manipulate his plans and actions, or his strategy and tactics. Or undermine his plans, undermine his strategy. If you don’t have this, then how are you going to shape his perceptions? You can’t do it. That’s why it’s important.

Of course, obviously you want to give him a rather incorrect or corrupt perception of the world so he can’t cope. Then, attack enemy’s plans is the best policy. Or attack his strategy is the best policy. Next best is disrupt his alliances, in other words split him up, another variation of what? Split him up, another variation of strength against weakness. Third best is attack his army. In any case, before you attack his army, you want to do all the other things, because then you put the army in what? A weakened condition, so it comes unglued. And then attack cities only when there’s no alternative. For anybody who’s fought in a city, infantrymen, oooooohhh, that’s mean stuff. It was mean in his day, it still is today, even though the instruments have changed.

And then he talks about these ''cheng/chi'' maneuvers, as the basis of throwing your strength against his weaknesses. So it raises the question, what do I mean by ''cheng''? Well he used some gifted language there, you read into it though, one’s the ordinary, and the other’s extraordinary. ''Cheng'' is the ordinary, ''chi'' is the extraordinary. You can also think of ''cheng'' as being the direct, and ''chi'' as being the indirect. ''Cheng'' is being the obvious, ''chi'' is being the hidden. More in that sense: ''Cheng'' being the deception, ''chi'' is being the surprise. [unintelligible]

Different ways you can think about it. Think of physical, the moral and the physical. In other words, it’s the combination that permits you to get leverage. If you don’t have the ''cheng'', then how are you going to be able to set up the ''chi''? Think, when you’re trying to use the ''cheng'' to get them to expose themselves, so you can run through that exposure.

In other words, it’s like a variation of what we call today, what? Anybody? Combined arms. What’s the virtue of combined arms, in the physical sense? You use one arm, so a guy tries to defend himself against one arm, it makes him vulnerable to another arm. Or vice versa. There may be a better term than combined arms, I don’t think we’ll use them. They’re complimentary arms, you’re really talking about complimentary arms. Use one, it acts as the ''cheng'' to get his attention, as a result, by trying to deal with one, he makes himself vulnerable to another one.

So when you’re using combined arms, in a sense if you do it correctly, you’re doing the ''cheng/chi'' game. And the desired outcome: you want to win the whole nine yards without fighting. Subdue the enemy without fighting. In any case, avoid a protracted war. You should see all the reasons why he wanted to avoid a protracted war. But then you got to give Mao credit. I’ll preempt myself, he understood it, as we’ll see.

Obviously the regime doesn’t want a protracted war, but what about the people going against the regime? If they can promote a protracted war, and the regime can’t handle it, they’re going to come unglued. Beautiful logic. That’s why it’s the guerrillas’ point to run a protracted war, if you can run a protracted war, Christ, they say the goddamn regime’s corrupt, incompetent, can’t even put these guys down, they’re supposed to be defending it. ''[15:00]''Just pulling the regime’s socks down, drop by drop, piece by piece.

Remember, that’s from the regime’s viewpoint, avoid protracted war. From the other guy’s viewpoint, not the regime, the other part say, hey, that’s good, they can’t handle it, we’ll embarrass them, looks like they don’t know what the hell they’re doing.

Audience: Sir, clarification so you don’t lose me, your comment on dispersion and concentration.

Boyd: I’ll get into it deeper later on, but go ahead.

Audience: Looking at it as viewed from the commander, if he concentrates his force, that implies mass, but if you’re looking at concentrating forces, that could imply dispersion then.

That’s a different—

Boyd: Yeah, but you didn’t say “force”, you said “forces.”

Audience: Yes, sir, but then you directly said, do concentration to the principles of war, mass, and if you look at—

Boyd: No, you said, principles of war, mass. I didn’t, so therefore why use it then? You just use the term.

Audience: But concentration to me, looking at a commander, if you look at concentration of “forces,” that implies maybe a mass, maybe the mass of the entire force, or a dispersion. If that’s where I’m wrong, I’m trying to follow—

Boyd: That’s alright. But I prefer not to use the word “concentration” because of the excess baggage it carries to this day. It carries a lot of excess baggage.

What’s the virtue of multiple thrusts, since we’re on this? Why do you want multiple thrusts? What if everybody goes up in the line together? Like we were just discussing before we came in here, since you raised the point. If everybody moves together forward, they’re all in line together, how, if the whole line moves forward, how can you get at the other guy’s flank? You’re just going push his line back. He says, we’re going to attack his flank. No, all you do is just push him back and have casualties.

So you want these thrusts going in there, because wait a minute, you got a flank too, you’re trying to get at his flank. That’s right. It’s true you got a flank. It’s not that you’re trying to get at a flank, the key thing is an exposed flank. If I got a tempo or rhythm faster than my adversary,

and I’m penetrating, he doesn’t know where the flanks are, you do, you’re carving him up, he can’t carve you up. The issue’s not flanks, exposed flanks are the issue.

And so if you have a lot of ambiguity and deception, you’re running on through there, you’re going pull him apart. Go look at the German campaigns or Russian campaigns, et cetera, all those thrusts that are going in there. And then look at the reaction of the people: they come unglued, they don’t know what the hell’s going on. Very powerful.

As a matter of fact, so I won’t forget it, the initial plan for Normandy, you only had three thrusts going in there. Montgomery, to his credit, complained like hell. People got mad at Montgomery, but he said, “hey, wait a minute, this is pretty goddamn risky,” he forced them to add two more.

They had five going in there. Because what you do is you generate what? More and more ambiguity in the adversary’s mind of what’s going on. You slow down his tempo to respond to that correctly, even on the spot, let alone in the fact that, we’ll talk about later on, the tremendous deception campaign where they locked up a lot of the Germans at Pas-de-Calais area. Very important.