Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

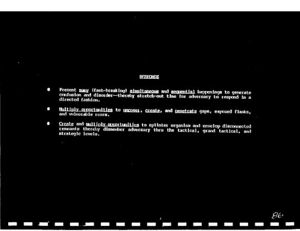

But here’s the reason why. Because when you have all that stuff thundering through there, you’re presenting many simultaneous and sequential happenings to generate confusion and disorder. In other words, the other guy really doesn’t understand what’s going on, so you stretch out his time to respond to react. He doesn’t know what to do. You’re stretching out his time.

You’re stretching out his OODA loop.

Therefore, you’re also multiplying your opportunities, to create and penetrate gaps. Remember, you’ve got multiple thrusts through there. If you’ve only got one and you happen to hit a strength, it’s over. You’re done.

If you have multiples going, some are going to get hung up, some leak through, and at that point you start shifting or emphasizing schwerpunkt where they’re going to go. And the other guys just keep the other guy’s attention. Hold them by the nose and kick them in the ass. Well, except you’ve got multiple hold ‘em by the nose and kick ‘em in the ass. Not just one. You’ve got multiples. Hold them by the noses and kick ‘em in the asses, you want to use a Patton-esque expression.

That’s what you’re doing. So by doing that, what’s happened, you’re creating multiple opportunities to split apart and envelop disconnected remnants. In other words, you’re generating, what, many non-cooperative centers of gravity, multiple non-cooperative centers of gravity, so they can’t function as an organic whole.

And that’s the power. That is the power. Go back and read World War I where Foch tried those massive offenses, everybody grouped together. They went nowhere. Go ahead.

Audience: Well, one question, the maneuver warfare we’ve been studying all year, [05:00] part of it is to enable us to react and to fight a force that is going to be numerically superior than we are going to be. Now what this is telling me, I could be wrong in my perception of how I’m reading this, is that number one, to have all these splinter groups and splinter thrusts you’re talking about, we’re going to have to have the forces to do that. In other words, we’re going to have to have a large force. What if, in fact, you don’t have the large force?

Boyd: You can still have multiple thrusts. You’re just going to have it projected against only a part of him rather than against a huge part of him. That’s all. A good example, what Balck did, and I’ll give you a good example. When he was in Hungary in 1944 or ’45. I can’t remember the year.

Wyly: I think it was ’45?

Boyd: I think it was ’45. Anyways, that’s when they were being pushed back by the Russians. So you can look at the dates. And so that was pointed out for him. They said, well, Christ, one time you have eleven divisions— he was going against Russians. He only had three divisions. And they said, well, Christ, how did you defend?

He says, no way you can defend, Balck said. They said, well, how did you defend? He said I didn’t defend. I attacked. Then he rolled up the whole Russian front. He’d come in with multiple thrusts and rolled them up from left to right or right to left, I don’t know.

Audience: Even when the—

Boyd: And he was outnumbered better than three to one. And he made the attack. Well, that Clausewitzian bullshit that the defense is a stronger form, that’s horseshit. Not only that—

Audience: Van Creveld, in his Command in War —[1]

[Cross talk]

Boyd: Not only that is, I don’t know if you read Clausewitz, not only that, he even contradicts himself. Because later on, when he talks about the mountains, remember, he says first of all, defense is the stronger form. Then he gets in the mountains, which is rough terrain. Then he says the offense is the stronger form. Well, he’s already got a contradiction.

Then he gets in the forest, and he’s a little bit more clever. I read that very carefully. He’s sort of saying the offense is the stronger form, but he couldn’t say it. But what he’s really saying then, the offense or defense, whether one’s stronger than the other depends upon the situation, whether it be terrain or people and that.

So therefore, if it depends upon the situation, then you say, why do you say it’s a stronger form?

The stronger form depends upon what’s the situation. Whether you’re going to use the offense or defense depends upon the situation.

But he didn’t say it that way, because he had to have an absolute notion. That’s horseshit. Even in his own book, if you read carefully, he’s got it wrong. And then he says, act with the utmost concentration, there is no higher principle. Then you go back in book eight, chapter nine, he gives four exceptions. The reason why, is because speed. You want to be fast, and there’s no

exceptions to speed. Well, if that’s the case, then speed is a higher principle than concentration. Once again, another contradiction.

If you don’t believe me, get the goddamn, you’ll see. It’s right there. But see, what he does, he’s got a very goddamn heavy logic, and when you go through it and you try to go through his logic in his sense, pretty soon you get sucked into it. You can’t think anymore. I found myself doing that. So I said okay. Now I’ve got to think in the outside. Hey, this is horseshit. Contradictions.

Now it doesn’t mean he didn’t have some good ideas. But I’m saying you can’t take that whole thing. Because this crazy notion, that defense is a stronger form, if it is, then how come he says that the offense is stronger in the mountains? And he sort of alludes it’s stronger in the forest. Then he makes some other comments in there, well, if the other guys— if you got more morale and the other guy’s got less, it also may be the offense may be stronger.

Then you say, well, since the defense isn’t the stronger form, then the offense is. But you can’t say that either. Which one you’re going to use is going to be dependent upon the situation. And in Balck’s cases, he said there’s no way I can defend with three divisions. I’m going to get cleaned. So he got a surprise attack, cleaned up the attack.

I mean, later on, they rebriefed their forces, pushed them back. But he stopped that whole operation they were setting up against him. So in that case, defense wasn’t the stronger form. His attack or offensive was the stronger form. So don’t believe that baloney. Read it carefully.

That’s what’s wrong with Harry Summers. He read that goddamn Clausewitz. Pretty soon he’s got this goddamn prism. He can only go through a Clausewitzian prism. He doesn’t understand what’s going on in the world.

We won all the battles in Vietnam. He says we won every battle. That’s bullshit. We lost the battle on the home front. Wasn’t that a battle? He said yeah, that was the most important battle. We had to come home.

So if you’re going to use battle as a measure of merit, be sure you don’t just narrowly truncate, it’s only for out in the field, there’s no other battles. If you’re going to use a measure of merit, you’ve got to be sure that it encompasses all the moral, the mental, and the physical phenomena. Otherwise it’s a horseshit maneuver. I mean, a horseshit measure. So don’t let people dazzle you with that crap.

And so you can see what’s happening here. You’re generating these many non-cooperative centers of gravity so you pull them apart. Okay, and then, which lead to this.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 34 Martin van Creveld, ''Command in War'' (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).