Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

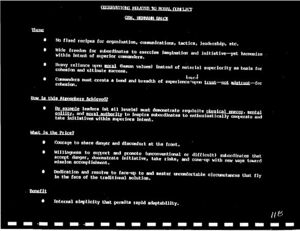

With that in mind, let's look at the moral, some moral issues here. And I got this from Balck, very good. And what he makes very clear, this theme. No fixed recipe for organization, communication, tactics, and leadership. Variety. Remember, you want to remain unpredictable and he makes that very clear. Wide freedom for subordinates to exercise imagination, yet harmonize within intent of superior commanders. Brings that over. Heavy reliance upon moral, instead of material superiority, as basis for cohesion and ultimate success. And what he says is that commanders must create a bond and breadth of experience based upon trust, not mistrust.

Most important thing you can do is build up bonds of trust between the commander and subordinates, or among the subordinates themselves. Because when you do that, then you've got an organic whole. And if you don't do it, you don't have it. And when the squeeze comes on, you're going to come apart.

Well, how is this atmosphere achieved? I only know one way, by example. The leaders have to set the example. If they're going to be a leader, they're going to have to set the example. If they don't want to set the example, kick the bastards out. Or at least don't put them in a situation that goddamn, is going to pull you apart. You have to set the example if you want to run the show.

If you want to be good, and you like to win, which I sort of, I think that's more attractive than losing. I don't know why I have that funny feeling. It's a lot more fun winning than losing. So that's the only way. You have to have the physical energy, mental agility, and moral authority. Which leads back to the trust. When it's mistrust, you’ve lost your moral authority, there's none there.

Remember a few years back, they wanted to have morale officers. There's only one guy responsible for morale, and who's that?

Audience: The commander.

Boyd: Goddamn right. And if you have to have a morale officer, the commander just said he doesn’t know what the hell he's doing. That's exactly right.

So what is the price? There really isn’t a price, got to use those words. Courage to share danger and discomfort at the front. You've got to be able to share that with your people. To understand what they're going up, also they respect you if you're willing to do that, and they understand you're out there playing the game, too. Also to get a feeling for what the hell is going on.

Willingness to support and promote unconventional or difficult subordinates that accept danger, demonstrate initiative, take risk, come up with new ideas, et cetera, et cetera. [20:00] In fact, in an old German equivalent to our OER—Officer Effectiveness Report—they had a code word in there, they put in there when they wanted a guy to get promoted. This guy is a “difficult subordinate.” That meant promote early. In our system, it's “two.” Because they recognize when you get this kind of guy with these kinds of characteristics, he's going to be difficult because the system is not used to it. He's trying to change ways. To make them better. He's a pain in the ass to a lot of people. Because they get nice and comfortable doing things the same old way. They've got all these preconceptions in their mind. They're very comfortable with the way the world's going on. And so, this guy comes along, like, son of a bitch, get rid of him. Big mistake. Huge mistake.

It's going to give your organization vitality. Now, you know, if he goes too far and gets a little bit obstreperous, then you’ll have to hold him down. In the meantime, you're going to have to give him a little leash, give him some headway. Be possessed of vitality. That's your ability to thrive and grow. Win rather than lose. Be adaptable rather than rigid. Dedication and resolve, to face up— face up and master uncomfortable circumstances that fly in the face of the so-called traditional solution.

Now if you can do these things, the benefit is you'll have internal simplicity that permits rapid adaptability, because you'll have an organic whole. You can make those adjustments. If you don't, you're going to have to have detailed orders, move like molasses in January. Everybody going off in the wrong direction and you're still trying to control them. The one thing you don't have is the very thing you want, control.

See, those bonds of trust, that common outlook, that’s where your control exists. Not through having a guy slavishly do this, or do that, or do this. Treating him like an automaton or a robot. In fact, some of the latest management guys, they say your control exists— you read some of the management yourself, some I’m going to hit you with it: control exists through what?

Audience: Excellence.

Boyd: Through what? It's through your value system. Your systems of values are the things that are important. That's through your control exists. And if you've got that common theme, you've got control. And our management people are just beginning to wake up to that, some of them. I won't say all of them. Go ahead.

Audience: We have a guerrilla war to fight with the American people on that issue.

Boyd: A friendly guerrilla war.

Audience: Well, a friendly guerrilla war.

Boyd: I understand what you're saying, but we don't want to make it hostile. It's a friendly guerrilla war. I understand what you’re saying.

Audience: It’s one that has to be not fought, or else we cannot, we can’t act if—

Boyd: No problem. But we got to inculcate that, but it’s what I call a friendly guerrilla war. We

don’t want to make enemies of them, but we’re going to say hey, there’s a game that can be played here and we’re all part of the team. I mean, I think that's what you're suggesting, right? Did I misread you? I hope I didn’t misread you. Maybe I did.

Audience: No, I don't think so. The President was recently criticized, President Reagan, for having that style of management, and that was the same style of management. In other words, he delegated, he had a value system [unintelligible].

Boyd: As long as you hold the value system.

Audience: When his subordinates, when one of his difficult subordinates got difficult, the American people then have to understand, well, this is going to happen, he's now going to take that under control.

Boyd: Reagan has been admired for defending his subordinates. He might have made some mistakes, but one thing he's been admired for is generally for defending his subordinates. Sometimes he might have gone too far, but if the guy’s a bastard and he’s violating— see, if a guy violates those value systems too, you know, he's earned discipline then, you know, stringent measures against him, because you've given him an opportunity to act in that value system. You give him freedom of action. If he goes against that, you know, you can't give him a free load, because other people are going to do it and the whole thing comes apart.

Audience: The guerrilla war you’re talking about, is the press on the side of, you don’t know what your people are doing? The press should take the side of, well, nobody can know what

everybody’s doing all the time, all they’re doing is exercising the—

Boyd: But then we have to educate the press. Say, look, do you know all of your editors? I can hit the press back. Oh, you're one of these goddamned geniuses. You know exactly everything that's going on in your paper, huh? You do know that, Mr. Reporter? Of course, he has to say no.

Then I say, why do you expect me to then? You know, put him on the goddamn defense and stick it up their rear. They don't know either.

Audience: Maybe I took it out of context when you said impose the value systems. I don’t think— it’s fruitless. You don’t want to impose values. That's a relative note of importance to that individual, like you were alluding to earlier.

[Cross talk]

Boyd: You don't. You don't want to impose it, but you want to show them a set of values that's going to be beneficial to them as well as yourself in that. That's what's got to be done. In other words, they got to readily accept those values. They got to be able to inculcate it within themselves, and that can be done.

Audience:[25:00] Well, a friendly guerrilla war because—

Boyd: That's why I call a friendly guerrilla war—

Audience: —we all have those values. It's just— it's sort of like the same issue with Wright. When we accept them, when it’s going our way, we notice [unintelligible].

Boyd: That's right. But see, there's a lot of people there, that's what I'm trying to say. So if you wind up where a little group gets the benefit and everybody else is getting screwed, they've got to go. You can’t do that. You're going to pull the organization apart. That's like having cliques.

That's what hurts organizations. You get a little clique inside, and they're taking care of themselves and opposing everybody else, but trying to make it look otherwise. We've seen that, and I've seen it in other organizations that fail. Okay?