Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

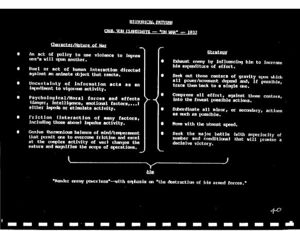

Okay. Now let’s go on to the philosopher of war, Clausewitz. He made that famous statement where he talked about the character, act of policy, to use violence to impose one’s will upon another. Later on he made the statement, not only war is politics by other means. We’ve all heard him say war’s an instrument of policy.

Anybody see anything wrong with that? The military’s an instrument of policy. When you say

something’s an instrument, what are you really inferring? You’ve got control over it. In other words, you’ve got— you know, a tool or an instrument, you’ve got control of it. But you can’t control war. You might be able to control the military as an instrument. Maybe not too much but [unintelligible]. You can never say it’s an instrument of policy, an act of policy, already you went too far. It’s not an instrument of policy. That presumes you can decide what’s going to

happen during it. You can’t.

Maybe that was our problem. We wanted to make an instrument— we wanted to make the

Vietnam War an instrument of policy. I’m sure that the idea wasn’t to go in there and get kicked out.

Another statement he made which is good, duel or act of human interaction directed against an animate object that reacts. [20:00]The idea is you’re not sure how he’s going to react. And since you’re unsure how he’s going to react, that builds up the idea of uncertainty among other things, uncertainty of information acts as an impediment to vigorous activity.

Then he brings in very strongly the importance of psychological and moral forces and effects, since we’re talking about animate objects. Danger being one of them. Intelligence. Here he’s talking about not an intelligence service but mental intelligence and emotional factors. Emotional factors, courage, confidence. Fear, anxiety, alienation, being the negative ones. Courage, confidence, and esprit being the positive ones. They can go either way, either impede or stimulate, in fact, depending upon the circumstances.

And then he does a very interesting thing. He takes all the interaction of all these things and lumps them under the notion of friction. The interaction of many of these factors, including all those above. And because that’s all very complex, that tends to, what, impede activity. Overall, it impedes activity.

Anybody remember his famous statement? “Friction is the only concept”—I’m quoting him now—“is the only concept that more or less corresponds with those factors that distinguish real war from war on paper.”

The point is, if you haven't accounted for friction, you're not talking about real war. And he’s quite right, if you think about it. Because the way he looks at friction, you read it very carefully. He treats it almost the same way we treat the modern— the way we look at the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy. We talk about all natural processes generate entropy in the second law. He doesn’t treat it in a physics sense.

The way he’s looking at friction is the way we almost look at the way we use entropy today in the second law. So in a sense, his ideas were a precursor to the second law. And that’s laced throughout his book. And the fact that a commander has to overcome that friction. In fact, in a dialectic sense, he used genius as the opposite of friction to overcome that friction. The idea that genius at war, harmonious balance of mind and temperament that permit one to overcome that friction. And excel at that complex activity.

While they can’t change the character and nature of war, they can change the nature and magnify the scope of operations. And then strategy, his strategy, exhaust them to influence and increase the expenditure of effort, he brings it up over and over again.

And then, seek out those centers of gravity upon which all power and movement depend and if possible trace them back to a single one. Look at all those powers and see if you can ideally take it back to one. Then he squeezed it one more time. He said in that effort, compress all effort against those centers into the fewest possible actions. Still not satisfied, he gives it another squeeze. He says, subordinate all minor and secondary actions as much as possible in all this activity.

So by doing all these things, in a sense he’s in harmony with his idea of friction. What he’s trying to do is overcome his own internal friction. See what I’m saying? So he can deal with that.

And move with the utmost speed. We already talked about that. And seek out the major battles that will promise decisive victory.

His aim is quite simple, render your enemy powerless, with emphasis on the destruction of his armed force. Not only the armed force, but that was his emphasis. He also talked about capturing a city or taking a province or something like that, also to try to destroy your enemy’s will. But he says, this precedes or dominates the others. That’s how you prevail, destruction of his armed forces.

Okay. Let’s critique Clausewitz.