Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

I’ll let you read this and I’ll comment on it.

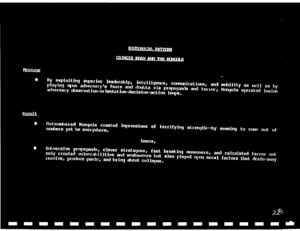

So if you can have all these kinds of things and your adversary doesn’t, you get inside his OODA loop here, they don’t get inside yours. You know what he’s about, he doesn’t know what you’re about. As a matter of fact, the Mongols were so good, they got so deep into their adversary, that down in Genoa and Venice, they knew where he was born in, Genoa and Venice, nations that didn’t know anything about the Mongols. So outnumbered Mongols, the result was pretty impressive, by seeming to come out of nowhere, yet be everywhere, hence all these things, and bring adversary’s collapse.

Well, why were they able to operate dispersed? Because they understood a fundamental truth here about those things. If you can operate at a faster tempo than your adversary, you can play the dispersion/concentration game at its widest possible sense. If you operate slower, you’re going to have to get concentrated, because otherwise you’re going to get torn to ribbons.

Not only that, Rommel understood that in the desert. The British complained down in 1942, 41, against Rommel, Christ, they were too spread out, that’s why Rommel was beating them.

Rommel was sometimes very spread out and sometimes concentrated too, but they didn’t realize he’s turning over his operations much more rapidly than the British, and pulling them apart.

How many people in here have read Clausewitz, anybody? You ought to read him. Book eight, chapter nine, where he has a long discussion about concentration and speed. In fact, he didn’t understand it himself. He says act with the utmost concentration, and later on he says it’s the highest possible principle. Maybe that why we got it as a principle of war, because it came out of Clausewitz.

But then when he goes into the discussion, he shows four exceptions on the idea of

concentration. [30:00]Four exceptions! Well, if it’s the highest principle, then why do you have an exception? Not only that, when he talks about speed, there’s no exceptions. He says act with the utmost speed, act with utmost concentration. But concentration’s the highest principle. And then when you read between the lines of concentration, if you can operate fast you don’t require to be concentrated. If that’s the case, then the premier idea’s speed, not concentration. Because with speed, you can play the dispersion/concentration game; in fact, you use it in order to concentrate on your adversary. So where in our principles of war do we have the principle of speed? Not there.

And that’s what the Mongols understood, they could operate— so Rommel and the other guys understood, and that’s why if you could set up a tempo or pace faster than your adversary, run

these multiple thrusts in there, you can get at the other guy’s exposed flank, so they are exposed, he can’t figure out what you’re up to, so you’re pulling his socks down and he’s not pulling your socks down.

So to get you the facility to play dispersion/concentration game in its widest possible sense by doing that, you can play dispersion against concentration like cheng and chi too. In other words, you can think of it as a variation on cheng and chi. Kick your guy, so he doesn’t know what you’re up to.

Go ahead, read. Book eight, chapter nine of Clausewitz. You’ll see it right there. Yet earlier on, he says it’s the highest possible principle. Well, if he finds out he can’t violate speed but he can violate concentration, tells me that speed is the highest principle. So that’s an internal

contradiction in his own goddamn treatise. You want to challenge me on it? I got the book right here and I’ll show you. So people say you got to act with the utmost concentration all the time and they say it’s the highest principle, I say then they don’t, I guess they’re not too accurate, mentally or otherwise.

That doesn’t mean you don’t operate concentrated sometimes. Remember, I said you could blend cheng and chi. And of course that was part of the argument. I tend to use the word “focus” rather than “concentration” because I think concentration has too much excess baggage. So I think we ought to get away from that goddamn idea of concentration because of the excess baggage.

Let’s put a new word in there, so we can define it the way we want to. And some people want to call it “focus of effort,” I would say, well, why don’t we use “focus of efforts” [unintelligible] so we be sure, that you know, we can play it in the widest possible sense. Give yourself more leverage against your adversary, deny him the opportunity of gaining leverage against you.

Because people, when you use a word, they tend to interpret it a certain way, so instead of actually giving you opportunity, it gives you constraint. And you want to design things so it gives you opportunity, not constraint, in so far as possible.

Audience: So to follow that, sometimes our terminology constrains us because it’s not general enough—

Boyd: It may not be intent to do it, but it’s an accident, but as soon as you see it, you better correct it. If you don’t, it’s just going go on, and it’s going goddamn grind itself in deeper and deeper. That’s why I always worry about words, sometimes I do it to myself, “hey, that’s bullshit,” all I’m doing is, I got to get rid of that and come up with something new, even though I don’t know what it is right now. And you’re always going to be doing that. Things change, that’s part of that variety and rapidity, you’re changing. You got to learn how to do that. Okay?

With that in mind, let’s move closer to the present.

Audience: Colonel, could I ask you a question on your last slide—

Boyd: Go ahead. Last slide—

Audience: Basically the idea of terror, in other words, scaring your enemy badly enough before you get there so far as to unhinge him, sort of like the British did in the Falklands, they said we’re bringing the Gurkhas, and they’re going to do bad things to the Argentinians when they catch them. Somewhere in your presentation, do you get to how we might use that today, given, you know, Congressional rules of engagement and media coverage [unintelligible]. One of the things you’re getting at with the Mongols here, is they terrorized people a long time before they actually showed up.

Boyd: Well, we’ve got things today called terrorists, as a matter of fact. We call them terrorists, state sponsored terrorism, et cetera. And the guerrillas used it very heavily. You got to be careful how you use it, I’ll be talking to that later on. One thing you want to do, you want to know your adversary; if you use terror, you also may tend to actually goddamn build up his resolve and cause you big problems then too. In other words, you unify him against you. So if you’re going to use that terror, you better understand how you’re going to use it. Will it really pull him apart, or is it going unify him against you? You just can’t say, well, we’re going to use terror, it may blow back on you like you wish you’d never had happened blow back on you.

[35:00]Even if you could do it. Right now we have a lot of constraints, I understand that. But even if you could, you still want to be very careful with that stuff. It can blow back on you. And not only that, you have a different world today. Remember, the world we talked about back in here, they could run an operation against some goddamn empire, some group, nobody else even heard about it because they didn’t have the communication. So by the time they heard about it, it was already over, plus they could control it much better. Today, with all the TV and mass communication, you do something like that, you’re in trouble. Remember, the world’s changed, we got to change whether we like it or not. If you just say bullshit, I’m going still do the same, you’re still operating back in an earlier century and you’re going get cleaned. You’re going get taken out.

Audience: Sir, I think what he was suggesting was that some of the things the Mongols did, terror, propaganda and so forth, are inconsistent with American values. Can you address—

Boyd: Oh, I understand that. I understand that. And I will address that.

Audience: Okay.

Boyd: If you’re going, see, here’s the bad part of— Go ahead.

Audience: To me, sir, that leads to us being very predictable.

Boyd: Not necessarily. You mean if we can’t do terror, we’re predictable? There’s many other avenues you can operate on. And remember, if you use terror, remember, we put ourselves up in the world being true to our vision. We got our Declaration of Independence, our Constitution, all that, so that if we go against it, all you’re going to, you’re going alienate the rest of the people.

Those dirty bastards, they say one thing and they do another. And I’ll get into that later on. That’s a moral issue, and you get taken out on a moral issue if you do that. And that’s the reason why you got to be very careful.

Audience: That’s what I’m getting at, is somewhere down the road—

Boyd: Yeah, my strategy, particularly in my strategy. I get into that moral issue, I don’t get deep into here, but my strategy I get very deep into that. And so if you say, I am this kind of a guy, you put, you know, television, TV, people out there all the time, and then you do something different. How would you like it if I were a friend of yours, or pretended to be a friend, and I tried to present myself one way, and I’m screwing you in the ass in a different way? You wouldn’t like it after a while, would you?

Well, guess what, nations are the same way. If you present yourself one way, start doing something else, you’re going to alienate yourself from other people. We’re the ones that subscribe to those values, now are we going stick to them, or are we going become terrorists, and we got to erase all that goddamn stuff and get down in the gutter with those other bastards.

I have a long— Mike knows in my strategy pitch I take that stuff head on, because I lay it out how the subtle twangs can get you in deep trouble. I can give you hint of it right now. Do you like a person that promises one thing and delivers something else? What if I tell you one thing all the time, and I’m doing something else? You wouldn’t have much respect for me, would you?

In a sense that’s what you’re doing, but in a much sharper, harsher sense. Now, it may be justified under very extreme circumstances, and you can justify it, fine; but as a basis of operations without those extreme circumstances, you’re going be in deep trouble. In other words, thou shalt not kill. We believe that except we go to war, we’ve got to go. But in the meantime, we understand, we’ve got that written in, we have to do that. And we’re only going to do that under very certain kind of circumstances. And if you’re going do terror, you can only do that under very certain kind of circumstances, and particularly the way we look at the world, we’re going be more constrained with that than many other people, as you’ve already cited. But that doesn’t mean we have to throw the towel in. Did I see another hand?

Audience: Terror is also a word, sir, that carries a lot of excess baggage with it—

Boyd: That’s correct—

Audience: —and we’re just trying to get inside the decision loop and create this confusion and chaos—

Boyd: —that can be regardless of terror—

Audience: —that’s the terror—

Boyd: If I get inside the guy’s decision loop, he starts coming unglued. He’s terrified.

Audience: Well, that’s exactly what I was getting at, in a case like in the Falklands, the British said we’re bringing the Gurhkas—

Boyd: I know, because people really fear the Gurkhas, that’s right, I understand. It’s probably the Latin mentality maybe more than other kinds of mentalities. I don’t know, maybe I’m being racist and I shouldn’t be, but my suspicion, from what I hear, being an American, I guess I’ve been preprogrammed, they tend to be more emotional.