Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

I’ll let you read these, and then I’ll talk [unintelligible]. You notice I took quotes here in both cases because they’re so nicely written [unintelligible].

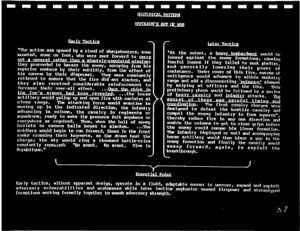

[05:00]When I’m talking about earlier tactics, I didn’t say it changed all of a sudden. In other words, there was a process [unintelligible] early on these tactics, and later on these tactics, in other words they transpired over a period of time.

[long pause as audience reads slide]

Okay, let’s discuss this. Note the underlines here, these two underlines actually capture the whole essence of the thing. Note what he’s saying: carry out a general, rather than a regulated mission. If I have a general rather than a regulated, what does that provide me? It allows you to be adaptable. If you’re regulated, you’re non-adaptable. With that adaptability then, then you can go after the chink in your foe’s armor, in other words strength against weakness. So the idea here is adaptability, strength against weakness. That’s the whole message of the whole thing.

Over here, note, heavy bombardment, strength going against strength. Now, everything’s

carefully timed. What’s an example of that people are trying to promulgate today? The Army, everybody’s seen the Army Field Manual 100-5? “Synchronization.” How in the hell do you synchronize human beings?

Remember, they’ve got those four things up front: depth, synchronization, agility, and initiative. Agility and initiative are good. Depth, there’s nothing wrong with it, except it’s in the wrong part of the manual, it should be in the back, getting lower with agility and initiative.

Synchronization’s a disaster. You don’t synchronize human beings, you synchronize watches. If harmony is higher, then they should use harmony instead of synchronization. Synchronization is part of harmony, but harmony is not necessarily part of synchronization. In other words, harmony is a more general term. It’s a mistake. So they still, goddamn it, haven’t learned their lesson yet. Then they say, “well, we didn’t mean it.” I said, “then take it out! Then why is it in

there?” Not only that, it doesn’t fit with initiative or agility. Initiative and agility are human terms, synchronization’s a mechanical term.

Now do machines fight a war, or human beings? Remember, they’re putting up front their philosophy. I’ll tell them right to their face, it’s bullshit. You got to learn how to use that noodle. If they want, they can put something else up here, okay, but you know, it doesn’t go alongside.

You don’t synchronize human beings. That’s not saying you shouldn’t synchronize watches, I’m not against that. Once in a while, you want a very tight synchronization with the artillery coming in on a time, on target, or something like that, but you don’t synchronize human beings. You want to talk about artillery, synchronizing watches or something like that.

If you use the word “harmony,” you can use the word “synchronization” later on and guess what, it’s in accord with harmony because it’s a subset of harmony, but it’s not all of harmony. They got to get that through their goddamn heads! Synchronization’s a subset of harmony, doesn’t

mean you shouldn’t have it, but it’s a subset, it does not go for human beings. Anybody who tells they’re going to synchronize me, I get personally irritated.

Okay, so that’s the problem, you see, careful timing. Well, Christ, we’re in a war of confusion, how are you going to be careful timing, that’s bullshit. So there, sort of here’s the essential point.

I guess they like this part. I guess that’s what they read in Napoleon. That’s the pervasive part that came down, comes out in synchronization now. I’m sorry [unintelligible] essential point, all I’m doing is I’m just [unintelligible] essential point.

Audience: But also doesn’t 100-5 on synchronization— Your point’s well taken, I agree with it completely, sir, but synchronization is, they also refer to it as the state of mind of the commander when he’s developing his plan, to consider the application of everything. [10:00]There’s one little statement in there—

Boyd: Oh, they’re going synchronize everything—

Audience: No, I mean, he’s considering things—

Boyd: He’s considering— I want him to use harmony, he can put the synchronization down in a subset. You can’t know everything of what his troops are going do. Otherwise you’re going go against the very— what he’s going do is lay down what he wants done. They’re going determine how it’s going be carried out. He’s not going know the infinite details, if he tries to get in there, he’s going screw up the operation, period. We’ve done that over and over again. I guess these generals, I don’t know what the hell they’re thinking about, because they ran a platoon one time, twenty years earlier, I guess they still want to fight at the platoon level. Did you know Patton criticized his guy? He told a colonel, “goddamn it, I don’t want you to interfere with their tactics.

You just tell them what they’re supposed to do, and they’re going do it, and that’s your jo. Be sure they get the resources,” he told his colonels. Quote. He said, “all you’re going do is muck it up.” He understood that. Can’t say he wasn’t a successful commander. He says, “all you’re going do is muck it up.”

Audience: Colonel Boyd, didn’t we start doing that though, during the Korean War, with nuclear weapons and communications were better—

Boyd: You’re raising a very crucial point. I think what you—You’re on to it, I normally bring it out. It’s a very good point you’re raising there. What’s happened, because of the rise of nuclear weapons and communications— Well, of course, we had communications during World War II—

Audience: But they weren’t as good as ours today, were they—

Boyd: Communication, radio, I mean they’re not as good as today. But of course, twenty years from now they’ll be better than we have today, too. But I mean, they’re not like World War I or

previous communications. But the point I’m trying to bring out with the advent of nuclear weapons and also the communications: boy they didn’t want some guy flinging off nuclear

weapons, so they had very tight control, because it’s an awesome weapon. And they should. But you shouldn’t— because you have it at nuclear weapons, you want to have it at all other levels.

Once again, that’s a rigidity of mind.

Audience: But since the Korean War, take the company commander. His power, or whatever he had, has declined because of those two areas. One time, I think the company commander—

Boyd: You know, if you want to give an order, you can always give an order. What you want to do is, you want to tell somebody what you expect. Let them determine how it’s going to be carried out. You should also tell them why you want it done. You know, so they can see that there’s a reason for it, not some goddamn bullshit in itself. And then you should put in, also, let them determine how, what, why, determine how. And then you should put in whatever

constraints that you want, because remember, you’re probably going deposit this thing in a larger context, and if they start doing anything they want, it can cause you some problems. So you should put constraints. Unfortunately, what we do is make the constraints so goddamn narrow, the guy can only do one thing, so therefore he’s got no freedom of action.

Audience: All those things you just said, you know, give the guy an order, let him do it how he wants, that’s what we’re told in school.

Boyd: That’s correct.

Audience: But then we have speakers come in, and—

Boyd: I understand—

Audience: —low intensity conflict for instance—

Boyd: I know exactly what you’re telling me. “Oh, we agree with you,” and then they tell you, and Christ, you don’t have any freedom of action. That’s exactly right. In other words, they’re telling you one thing, saying one thing but they’re doing another. In other words, it’s a huge goddamn deception operation. On you! [audience laughter] You’re the object of the deception.

You don’t have to do that.

I’ll give you a good example of when I was overseas, of how they wanted me to do it. I was initially—you raise a point, the reason I’m going to bring it out, it’s an interesting point that came up—I was sent over to Task Force Alpha. You probably know that was the old sensor program, sometimes called Igloo White or some other names. People didn’t like [unintelligible]. In any case, over in southeast Asia.

In any case, one night— eventually they made me base commander. They went through seven base commander in two years. They said, “Boyd, you got to clean it up there.” I didn’t want the job, hell I don’t want this goddamn, but I had to take it over. Well, one night I’d been there for— hell, I didn’t even know what my responsibilities were, so—a couple of our electric goons, those spy C-47s crashed, listening and ELINT[1] gear and all that on there [unintelligible]. Of course, guys are out there in areas where there might be guerrillas and that, those people sent us some choppers.

So the guy says, “you’re the commander on the spot.” Now I hadn’t been there too long. I said “I am?” He says, “yeah, okay let’s go down.” And he said, “here’s your checklist.” I goddamn near fell over. I said, “what do you mean, checklist?” I took that goddamn thing and threw it, it went out the window. I said, “now where’s a map, let’s find out where they are, and let’s start making some decisions.” The guy brought the checklist back in, and I threw it back out the goddamn window. Some captain. I said, “you can’t operate this way.” They don’t know, you know, I said, “if I read this, those guys’ will die of starvation out there before we get to them.”

So I said, “now where’s the map?” I said, “get that goddamn thing out. You point where they

are.” They said, “We don’t know.” I said, “Who knows?” He said, “we’ll find out. We’re on

that.” I said, “fine. What resources do we have available?” I’m going to take the choppers out

there, then we found out we don’t have enough choppers, so they had a [unintelligible] They

said, “Yeah, but these guys got to go first.” Fuck that, I don’t care. I said, “What is the situation

out there?” [15:00]So I reversed the whole order, and sent the choppers out and everything else.

And he kept bringing the checklist back. I said, “I don’t give a goddamn to hell you’re

[unintelligible] you bring it back in here again.”

He said— you know, as the new guy. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. I got them all out. Blew up the two goons. You know, we had to blow them up because security [unintelligible] we got them all in there. I didn’t go by any goddamn checklist. I said, you know, what do you have, went down my way, and did things that had to be done.

If I started reading a checklist, hell, [unintelligible]. That’s bullshit. Of course, I’m a fighter pilot, I think that way. It’s just like he’s a fighter pilot back here, every year. I think they maybe still had it when I was there. They had this huge book. You got to sign about all the regulations that you’ve signed it, and so if you violate it, they can hand you your ass.

Well, nobody ever reads the son of a bitch, they just signed it and walk out the door and said “yeah, I read the son of a bitch.” That’s a huge deception. You still sign that bitch, don’t you?

[Cross talking]

Boyd: I bet it’s probably this goddamn thick now.

Audience: They’re a lot thicker now. You don’t sign anymore, sir. They just say you’re responsible for all these regulations, even some that you don’t know of. That’s the new way.

Boyd: Yeah. So everybody walked out. I said, “we’re all a bunch of goddamn liars.” We all go in here, great, sign, walk out the door. It would take thirty seconds. Nobody reads the son of a bitch. And they had this huge book. That was so if you violate something, they could hang your

ass and they got your name on it. That’s all it was for.

You really read that thing, you’d be here a week. Like he said, it’s even thicker now because they got more regulations in the meantime. It’s a huge thing. We all used to laugh. I’d say, “we’re all a bunch of goddamn liars.”

You go down there and stand in line [noise representing book pages turning] this huge book. Boy, you really walked up through there fast. It’s a disaster.

Okay. We look at Napoleon. Did I take you through that? Yeah. [unintelligible] I’m getting off track. Okay. Napoleon’s Art of War.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 13 Electronic intelligence.