Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

Boyd: That’s right. That’s right. Okay. Now the message then behind it. Let’s talk about this. Here’s the German concept of mission. You can kind of think of it as a contract between superior and subordinate, an agreement. Whereas, in a sense, the superior determines what is going to happen, but the subordinate determines how it’s going to be accomplished, as long as it’s within the superior intent.

In other words, he doesn’t tell him how to do it. As a matter of fact, let me give you a good example. Tell me, you people have heard of General Balck, haven’t you? Hermann Balck? He was one of the most successful Panzer commanders. We had him over here, I think, I can’t remember, 1981, or something like that.

We had him at the Pentagon, and we had him and the assistant secretary. We went through a long discussion. We had lunch in one of the nice dining rooms over here with one of the assistant secretaries.

And one of the guys said, “but how do you tell them to do stuff?” And Balck was insulted. He said “I don’t tell anybody how to do anything.” He said, “all we tell them is what has to be done and get an agreement upon it. They determine how it’s going to be carried out.”

He said, “well, what if you don’t like the way?” He said,” doesn’t make any difference whether I like it or not. He does it. I stand aside. The only thing I worry about is if I think it’s illogical, I won’t let him do it if it won’t work. But normally they know how. It might be different from mine, but if it’ll work, he does it that way. He determines how it’s going to be done. I just determine what’s going to be done.” He said, “what if it doesn’t work out?” “Well, if they do it a couple times and it doesn’t work out, we’re going to replace him with somebody else.”

But normally, when they pick those guys, they’ve observed them for a period of time. And then he gave a good example. He talked about this one guy he had who was an Austrian. I think he was an Austrian. Might not’ve been an Austrian. But— no, it was a German. And during the prewar exercises and all that, the guy was a basket case. He was terrible. Couldn’t do a goddamn thing right as a commander.

And so they kept him in the training thing all the time. Still, when they put him in the exercise, he couldn’t do it. So eventually they needed him, because they ran out of commanders. Well, we’ve got to throw him in. We’ll put him in a sort of a sector near the front. And he’s doing pretty good. So they put him in another sector.

The wildest thing, the guy’s doing better than any of the other commanders. So they said, now we’re going to send him back and show him how to— we want him to teach his methods to the guys in the back. Once again, he’s a basket case.

And I’ve seen the same thing among fighter pilots. I’ve seen them when I was out in Nellis.

Some guys, Christ, they didn’t know how to spell their name and how to tell anybody how to do anything, but they were fantastic. There’s an innate skill and they have it. They can get people’s esprit up. [20:00] But in peace time, they’re a basket case. And you see that.

He talked about this one guy. He said, every time, they couldn’t believe it. They figured, now he’s finally got the picture. Now he’s going to show our young people how to do it right. Oh, my God, he was a total disaster. Back to the front and did superb.

But that’s the kind of things you find out. You get those surprises from time to time. And I’m sure you’ve seen that in your people at different times.

Wyly: You know, there’s one other dimension tothat question you asked, that I think this needs to be brought out, about the German Army in World War II and van Creveld’s German Army now. And Marines can relate to this. Because in World War II, you talk to any German soldier that was in that army, and their esprit was just incredible.

Boyd: Even in the worst days.

Wyly: Oh, yeah. I mean, right down to some of the things that we call discipline, you know, the pride in being a soldier. And that has a lot to do with it. And I think that’s kind of what may’ve started some of this dialogue ten years ago. I had so many German officers say to me, you Marines ought to pick up on this, because you have a lot of what we had back in the days of the 100,000-man army before World War II.

Don’t forget that since World War II, a lot of that has just come apart because of the pacifism, the attitude, the understandable attitude of post-war German. So the “click of the heels” and a lot of those things that made all these other things come together, the esprit and the camaraderie, some of that’s gone. So it’s a different thing.

Yet on the other side of the coin, the German culture has placed a tremendous emphasis on education. John and I were talking about that. And I would say more so than Americans do. And that gives them a different outlook, and that probably keeps them a little stronger.

They’re weakened because they’ve lost some of the old military spirit, and that’s gone. And they’re going to have a tough time ever getting that back. But they’re strengthened because they still put an awful lot of emphasis on education, more so than our society does.

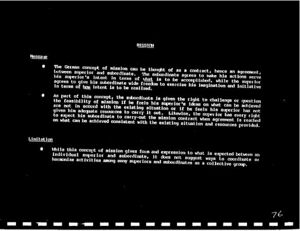

Boyd: But note this. Note that second bullet there. That’s the thing Mike was alluding to before. In other words, expect the subordinate to really throw his weight in there before the decision’s made. He’s given the right to challenge or question, the feasibility of mission if he feels his superior’s ideas on what can be achieved are not in accord with the existing situation, et cetera, et cetera. Or if he feels he’s not getting adequate resources.

He can challenge it. Expect it. We raised this to Balck. He says a lot of superiors don’t like it, but they know they’ve got to do it. Some of them would not go along with the spirit of it, he said it was bad. You’ve really got to go along with that. So be sure you bring in those ideas before you make that decision.

Once the decision is in place, though, then they’ve got to carry out the decision. So if they’re given this place, then likewise, of course, when you play that game, the superior has every right

to expect the subordinate to stay within that intent and carry out the decision because he’d been given that opportunity.

In other words, there’s sort of a contractual agreement there, is what I’m trying to tell you. There’s a two-way sway, not just a one-way sway. Think about it.

There’s a limitation. This is an important idea. I say, well, it gives form and expression to what was expected. What it really doesn’t do, how do you coordinate or harmonize activity among many superiors and subordinates? You still have to do that. Okay?

Audience: [unintelligible].