Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

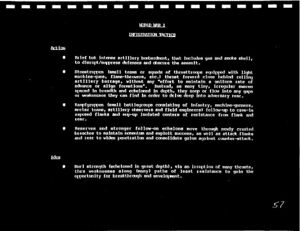

Okay. Now let’s look at some of these. First the guerrilla. I mean, excuse me, infiltration. What do you see here? Something very different since the 19th century. Note, rather than trying to use their artillery to destroy it first. And what are you doing? You’re trying to disrupt his defenses. And on the end, you have a short artillery barrage.

And if you think about it, the artillery now is being used for what? It’s in a sense— you can think in Sun Tzu’s term, it’s a cheng to the following effort which is the chi. You’d think it was a cheng/chi operation, which we discussed last night.

And in the follow-on, small teams here and the larger groups. In every case, look and note what they’re trying to do. They’re trying to use the Sun Tzu metaphor. Remember what I said last night? Behave like water. Flow through the gaps and crevices, the voids, et cetera. In other words, strength against weakness. Trying to flow through. [10:00]And note that they didn’t try to keep their formations nicely lined up. Each one tried to make his own pace through, not worrying about how fast or how slow the guy on the right or left of them are going. Work their way through.

And then the other teams coming in behind them, larger teams, isolating the local centers of resistance, and mopping them up from the flank and the rear. And then the larger units pouring through, these gaps get larger and larger, until you’ve got what Liddell Hart calls a torrent pouring through the front.

So it’s in great depth. And of course, then the idea is very simple: hurl strength based on great— by an irruption of many thrusts. Note the word. Not just a thrust but see, wiggling in through there. Multiple, many. Because see, if everybody goes through up on line— I don’t know— I’ve never figured out if everybody goes up on line, how do you get the other guy’s flank. You can’t get at a flank. In a sense you’ve got to present a flank in order to get at a flank. You say well,

then we’re in as bad of a position as he is. Not necessarily. The question is, who’s got the exposed flank? That’s the issue. Who’s got the exposed flank?

So if you can operate at a tempo or pace that he can’t keep up with, he can’t understand what’s going on. He’s disoriented and you’re not. He’s got the exposed flank. You pull his pants down.

He doesn’t pull yours down. You scarf up the prisoners. He doesn’t.

Audience: So an exposed flank—

Boyd: And in a sense, it’s like the Sun Tzu metaphor. And Patton, I mentioned him last night, he said that. Some guy’s worrying, he says, don’t give me any crap about your flanks. Let the other guy worry about his flanks. I know you’ve got a flank. Make him worry about his. Let him have the exposed flank. That’s Patton himself. He understood it. Another one he said, don’t give me crap about holding your position. You’ve heard that one.

He was a little more articulate. I think his language is a little more rough than what I use here, but the point is, that’s the essence of his message.

Audience: I don't understand what an exposed flank is then. Because you’re saying that is—

Boyd: Well, look at it.

Audience: —the force that doesn’t—

[Cross talking]

Boyd: If I can go through with multiple thrusts going through somebody, right, he’s going to be in these little areas here, right? Let’s say these are my thrusts. Right? I’ve got a flank here, flank here, flank here, flank here, don’t I?

Audience: I understand that.

Boyd: But he’s got flanks. The question is who’s got the exposed flank. And if you’re operating so fast he doesn’t understand what you’re doing, in a sense he’s exposed because he’s static here.

You can start pulling him apart. He’s not prepared for all these things being this way. It happened all of a sudden on him. You’re prepared because you’re in the operation doing it.

In fact, as I show you later on when we get into the blitzkrieg tactics, they talk about the rollout maneuver. You know, you had the thrusts and the rollout, or what the Germans call the off-roll.

So you got thrusts going in all these directions. You’re cutting them up.

Audience: Sir, I got a distractor going around my brain housing group. If Haig[1] had had the same observation and orientation of his frontline commanders, he would’ve seen that his movement was frivolous. Valid?

Boyd: Who? Who are you talking about? Haig. Oh, the Somme—

[Cross talking]

Audience: Yes, sir.

Boyd: Oh, okay. You’re talking about the Somme. Well, remember, he was sitting back in a chateau...

Audience: Yes, sir.

Boyd: —getting some radio reports. He didn’t go up and interact with the troops, and get the feel of what they could do. So he was divorced from what was going on. All he had was whatever he got in on these little pins that he’s sticking in a map, and his radio reports that he was getting.

So he didn’t really have a good impression what’s going on. It’s a false orientation. Yeah, I guess that’s your comment. He had an orientation, but his orientation was the orientation you get at a rear headquarters, period.

That’s a rear headquarters orientation. Unfortunately, it doesn’t map to what was going on up there. In fact, I think he was the one that said after the Battle of Passchendaele, he said if I had only known what had happened, I would never have sent the troops into this goddamn operation. Which means he already knew he had a faulty orientation.

And that’s why the commander’s got to get up there in order to talk to their people, in other words, get the feel for the way things, also the situation they’re facing there. So you don’t take them into situations that are, you know, catastrophic disasters, blunders, whatever you want to [unintelligible]. You’re still going to make mistakes, but you’ll minimize them. We’ll get into that later on. I don’t want to bring up too much right now. But you’re onto a good point.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 20 Sir Douglas Haig commanded the entirety of the British Expeditionary Force for the majority of World War I. He has often been criticized for the high level of casualties absorbed by the British army under his command and an apparent detachment from the reality of the conditions of the front lines, though recent historiography on these charges is more mixed.