Patterns of Conflict

| The works of |

| Works of John Boyd |

|---|

OODA WIKI Edition

Quantico Transcription

And these aren’t always the same, these all weren’t drawn up at the same time, they were drawn up at different times, but you’ll see in a minute, it feeds my argument.

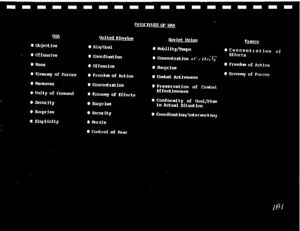

For U.S.A., you’ve seen these, United Kingdom, in fact ours are very similar to the United Kingdom, because actually we got them from J.F.C. Fuller and we’ve modified it a little bit, but basically are about the same. And the Soviet Union— but notice the Soviet Union, where we don’t have anything about speed or tempo, their first one is mobility and tempo. Where the hell did they get that? Because they got their head handed to them by the first part of the blitzkrieg, they didn’t have it before World War II.

Audience: Didn’t Fuller, after he wrote the “Principles of War,” shortly afterwards says all this is a bunch of—

Boyd: Yeah, after he put it together, he said, when he saw people were using it, he says toss it out, it’s bullshit. And then guess what we did, we went for it even harder. That’s exactly right, that’s exactly what Fuller did. I’m glad you mentioned that.

Wyly: In fact, J.F.C. Fuller waited years before he said toss it out, it’s bullshit. He kept changing them, and I think it was in 1925, we looked at them, and adopted them, and they’ve stayed in concrete ever since. So then he changed them for several years, and then finally, threw them all out.

Boyd: Yeah.

Wyly: And the American ones and the British ones initially looked exactly the same—

Boyd: I think they were exactly the same.

Wyly: In fact ours lasted longer, we kept his old ones longer than the British, the British list in 1925 would have been just like our list.

Boyd: Yeah.

Wyly: And ours stayed in concrete the longest.

Boyd: Now these were drawn up in the Soviet Union right after World War II. And any—how many—some of you people might have read some of those—used to have translated documents, The Operational Art, [35:00] they’ve got them listed in there, you know, the book by Savkin.[1] Are you familiar with the book I’m talking about by Savkin? And that’s where they’re laid, you can just look and you can see them all. And he has long goddamn dialectic conversations on them, most of it’s horseshit, but you know, if they don’t get— I think it’s about if they don’t have one-third of their document full of dialectical materialism, they won’t publish the thing.

And so you’ve got to work your way through all that baloney. It’s terrible stuff to read. You know, every time I read that stuff, I got to sit there every five minutes and say, “hang in there, Boyd, it’s going to better,” knowing it’s not. [audience laughter] Knowing that it’s not, it’s terrible. Drink a lot of coffee, “come on, tiger, it’s going to get better,” I’m giving myself a pep talk, knowing that it’s never going to get any better. I got to deceive myself.

And then France, you’ll see this, concentration of efforts, freedom of action, and economy of forces. In fact, they had different ones in their country. They argue about the, you know, the typical French, you know, different factions are going to have different principles of war.

And then of course the Germans—they might have them now—they didn’t even have any. Well, isn’t that interesting? They didn’t even have principles. I don’t know whether they do— do they have them now, I don’t even know?

Wyly: Not that I know of.

Boyd: They might, I figured after they might have learned from us, but they don’t even have principles. So the question is, you know, will the real principle stand up? Who’s right or who’s wrong, or what are we talking about here? And here’s my critique.

[Continues to Slide 182]

[flips back to Slide 181]

Christ, they’ve got input mixed up with output and all that. You look at it, they’ve got it all— this is us, this is us, or we’ll take this one, we get objective, offensive, mass, maneuver, security, surprise. That’s output. Some of them are your input, then they got output— they can’t even separate the input from the output. Surprise is what you’re getting the other guy, concentration is what you do. Same with Soviet Union, mobility, tempo, and surprise, output. I mean that’s what you’re trying to get out of your adversary. Mobility, that’s you.

So the whole thing is all gomered up. That’s my point. You see what I’m getting at? What do you do and what are you trying to get out the other guy? So it’s— let’s put it this way. It’s not too well thought out. Not very well thought out.

Lightfoot Transcription

- ↑ 45 V. Ye. Savkin, ''The Basic Principles of Operational Art and Tactics (A Soviet View)'' (Moscow, USSR: USSR Ministry of Defense, 1972).